A c t 2 S o , W h a t i s a C u r a t o r A n y w a y ?

|

SCENE 1: SO, WHAT IS A CURATOR ANYWAY? In the Makin Room, Bluecoat. Eddie talks to Jade whilst unpacking his lunch into the fridge as first workshop is about to begin. EDDIE: So, what is a curator anyway? I mean, I remember Sarah-Jayne [Bluecoat’s previous curator], but she doesn’t work here anymore. Couldn’t tell you what she did. |

A monumental question asked so casually, and at that particular moment, I had no answer. This brief interchange with Eddie on our very first workshop cuts to the heart of a key question within this study – what does a curator do, and why is there so much confusion about it? As discussed in Act 1: The Prologue, the curator’s role has diverged, expanded, become professionalised, and is more visible than ever before. But still curators are perceived to be somewhat elusive. Described even by those working in the arts as “working behind the scenes in an opaque job” (Neuendorf, 2016) and moving in “quiet and mysterious ways… with something tantamount to divine power.” (Robbins, 2005, p. 150). This ‘opaqueness’ surrounding the curator feeds into that sense of ‘mystery’ keenly observed by Eddie, and so it became my task for this study to demystify what a curator is by breaking down and interrogating the curatorial process itself.

In the first phase of this study which lasted for three months we focused on exploring what a curator is, but more importantly, what they do. Keeping in mind inclusive and participatory action research approaches, it was important for me as a facilitator and researcher to root exploration within ‘doing’ because for learning disabled people often “making sense has a lot to do with making” (Streeck, 1996, p. 383). Therefore our starting point was the gallery itself and for the first few months we visited as many examples of curator’s work ‘in action’. This meant meeting curators and visiting many exhibitions, galleries, studios, artistic interventions and a biennial across Liverpool. This included sites such as Tate Liverpool, FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), The World Museum, Museum of Liverpool, Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool Biennial (including temporary sites such as Cains Brewery and ABC Cinema), The Walker Art Gallery as well as regularly visiting the changing programme at Bluecoat. By doing this we aimed to research what artistically was happening around us and to observe different curatorial styles from different curators across different institutions.

visiting Galleries and museums

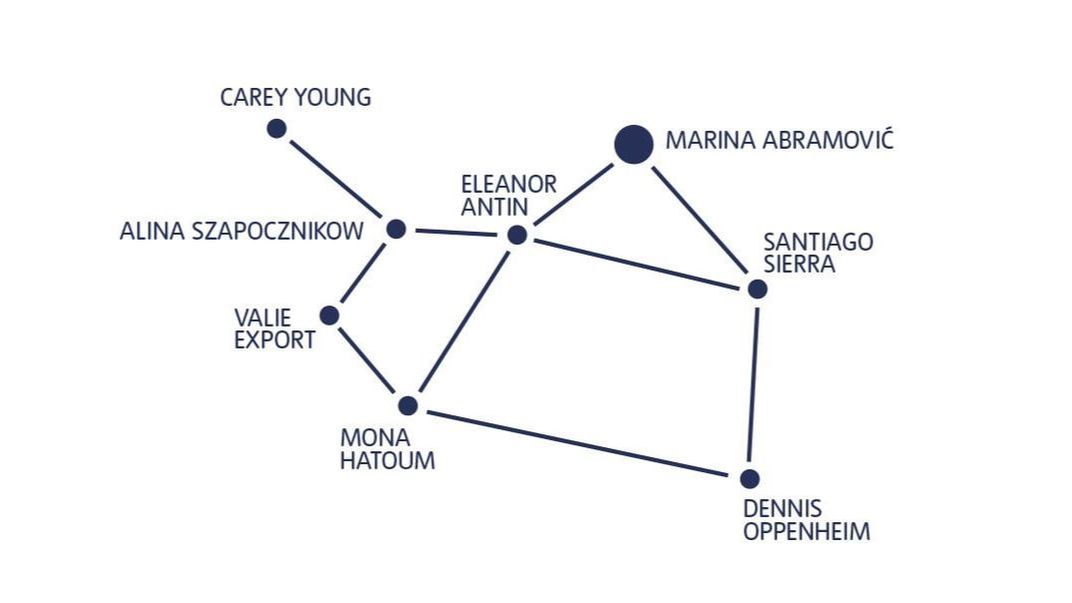

Whilst the group visited a range of exhibitions in this first research phase, I have chosen to discuss two visits in detail due to the central part they played in the project. Our first visit was to Tate Liverpool on 25th January 2016. At this time Tate Liverpool was exhibiting a large show from their permanent collection titled DLA Piper Series: Constellations in addition to a touring exhibition by Henri Matisse titled Mastisse in Focus. The DLA Piper Series: Constellations exhibition comprises of Tate's permanent collection. The exhibition has been curated to present artworks in ‘constellations’ or clusters, with special works selected to act as the originating ‘star’ of these constellations because of their “continuous revolutionary effect on modern and contemporary art” (Tate Liverpool, 2013). Each of the artworks are displayed among a group of artworks that relate to them, and to each other, often across time and location of origin, encouraging visitors to discover similarities between works of art that at first glance, may seem very different.

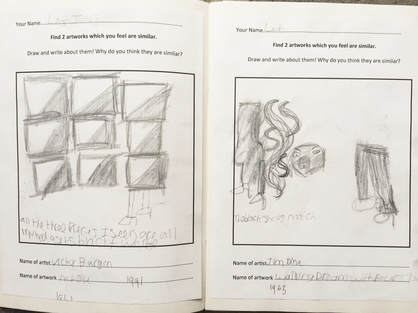

Leah's activity results

Leah's activity results

What interested me about this exhibition is that in its marketing and interpretation there appeared to be an assumption that both the gallery and curator has a duty to ‘educate’ the visitor. In the exhibition’s press release Tate Liverpool’s Executive Director Andrea Nixon claims that the show is “broadening visitors’ knowledge and understanding of modern and contemporary art” (ibid), whilst Artistic Director Francesco Manacorda states that the exhibition will “encourage visitors to ‘join the dots’ between artworks” (ibid). Curatorial practices in 19th century galleries and museums (practices that dominated well into the 20th century) echoed this description, “perceiving visitors to be deficient, lacking knowledge and in need of instruction” (Robbins, 2005, p. 151). Although attitudes have changed (Hein, 2008), there is still a sense in which curators appear to be responsible for providing special insight and knowledge to gallery and museum goers who require cultural education. I wondered how the group would relate this curatorial approach and whether an exhibition curated based on making links between art - historic, genre, political - would present a barrier for them. In preparation for our visit to Tate Liverpool I had designed some activities for the group. Responding to the exhibitions concept of ‘joining the dots between art’, for the first activity I asked the group to find two artworks which they thought had something in common, to sketch and describe them. Here, I wanted to see if the Tate’s curators’ intention of presenting artworks in 'clusters' was successful for the group, and to see the connections they would make on their own.

Leah chose a series of 9 black and white untitled photographs by Victor Burgin (1991) and a piece titled Walking Dream with Four Foot Clamp (1965) by Jim Dine. At first she said they were both black and white and that was her connection. When I returned to chat to Leah after she had been sketching a while, she had then noticed that the two pieces both features legs (I had not spotted that one of the photographs in the Burgin series was a close up of a woman's legs). She also told me they both were “made up of parts”. I was not sure what she meant by this at first but later I spotted that the painting of legs was actually not one canvas, but a triptych. Both artworks Leah had selected comprised sections of images arranged to appear as a whole

Leah chose a series of 9 black and white untitled photographs by Victor Burgin (1991) and a piece titled Walking Dream with Four Foot Clamp (1965) by Jim Dine. At first she said they were both black and white and that was her connection. When I returned to chat to Leah after she had been sketching a while, she had then noticed that the two pieces both features legs (I had not spotted that one of the photographs in the Burgin series was a close up of a woman's legs). She also told me they both were “made up of parts”. I was not sure what she meant by this at first but later I spotted that the painting of legs was actually not one canvas, but a triptych. Both artworks Leah had selected comprised sections of images arranged to appear as a whole

|

Diana was very drawn to the more traditional art in the exhibition and selected two paintings because they both featured portraits of men and were displayed in “special gold frames”. Hannah spent a lot of time drawing her first artwork which was a painting of a bedroom. Hannah struggled to understand the instructions to find something in connection to it and did not recognise the curators intended connection (described via text) regarding painting style. However, with one-on-one support she spotted a painting detailing the inside of a window, and so both of her selected artworks were paintings of domestic settings. When providing one-on-one support, often I am supporting someone to navigate a decision-making process. In this instance, Hannah needed support to break down the question of ‘finding two artworks with something in common’. Both Hannah and Diana needed further support to think beyond what the artwork depicted to thinking about what it could mean or the context it was made.

|

|

In complete contrast, Eddie selected a Christo sketch titled Christo’s Valley Curtain (For Colorado) depicting one of his famous swathes of material in a landscape. The similar artwork he chose was Man Ray’s L’Enigme d’Isidore Ducasse (1920, remade 1972), which essentially is a sewing machine wrapped in material and tied with string. Eddie was interested in the similar use of material but more so in the concepts of “hiding” and concealing. He asked a lot of questions about both of the artists’ intentions behind using the material and I sensed that for him there was a real connection in the 'why' behind the artwork.

Tony had a slightly different approach and chose to sketch the first artwork simply because he really liked it. It was a modern sculpture made of plastic which to him resembled a clock. After completing his sketch, he then decided to draw a wire and bronze sculpture. I assumed Tony had selected the second artwork because it too was a sculpture but instead he said that he chose as it was “futuristic” and modern “like the modern clock”. Tony seemed to be placing his own narrative on the sculptures – deciding on what they looked like and what they could be from the future. |

The concept underpinning the DLA Piper Series: Constellations exhibition is that art is connected; whether via artistic movements, time periods, politics, or technique; the underlying implication is this exhibition would offer visitors insight and education into these connections. Many curators employ this approach in that they curate work in a way that the art 'talks' to each other, so this was a key skill for the group to identify and develop. However, this desired curatorial approach did not entirely work for the group. The group made no connections between genres, times periods, artistic style or artist collectives as the exhibition intended. Instead the group focused on connections between materials, texture, colour and interestingly narrative; making interesting connections and not ones I would have seen myself as they were drawn from personal experiences. On the whole, their connections emerged from observable physical forms and stories which gave me a useful insight into how approach working with the group. From this I sensed the group would successfully be able to relate to artists and their work if I used personal experience as the starting point.

We then headed upstairs to see the next floor of the exhibition for which I had new activity planned. I asked the group to select and sketch one artwork – one artwork they did not like and would take out of the exhibition given the opportunity. I asked the group to do this activity as I feel often learning disabled artists are asked to think about what they do like but not often about what they do not like. This activity proved very difficult for the group. They all said they liked everything and “everything is good”. I found this, and still find it hard to believe! I very rarely like everything in an exhibition, there is usually an edit, however small, I would make. Their reaction however, did not surprise me. I have often found this when working with other learning disabled groups – there is often difficulty in expressing opinions about things they do not like. But why is this the case? Is it verbal skills? Critical skills? Or because when dislikes or negative emotions are expressed they are sometimes dismissed under the umbrella of ‘challenging behaviour’? Valerie Sinason, child psychotherapist and adult psychoanalyst specialising in learning disability, proposed a theory in the early 1990s called the “handicapped smile” (1992). This term refers to the habit of compliancy, happiness and smiling despite pain or negative emotions, in order to be accepted and maintain the status quo. This “outward sign of a psychic defence” (Lloyd, 2009, p.63) guards and disguises intense pain (for themselves and for others), “the body attempting to make a self-effacing apology for the mind within” (Fonagy, 1993, p.118). Whilst I am not convinced that this is necessarily the case, it was clear that as we looked at the role of the curator we also need to develop ideas of critical engagement. However with some support, everyone chose something that they would take out of the exhibition. It was here I identified something important in terms of my facilitation for this study. I learnt I needed to think carefully on how I frame critical questions to the group. Instead of asking the curators what they did not like and polarising their opinions automatically, I instead asked; 'which one would they edit out?' or 'which one doesn't work for what you're trying to say at the moment?' I took this approach forward to the next phase of the study when the curators are required to make selections or edits as 'liking' and 'disliking' are too simplistic for curating.

We then headed upstairs to see the next floor of the exhibition for which I had new activity planned. I asked the group to select and sketch one artwork – one artwork they did not like and would take out of the exhibition given the opportunity. I asked the group to do this activity as I feel often learning disabled artists are asked to think about what they do like but not often about what they do not like. This activity proved very difficult for the group. They all said they liked everything and “everything is good”. I found this, and still find it hard to believe! I very rarely like everything in an exhibition, there is usually an edit, however small, I would make. Their reaction however, did not surprise me. I have often found this when working with other learning disabled groups – there is often difficulty in expressing opinions about things they do not like. But why is this the case? Is it verbal skills? Critical skills? Or because when dislikes or negative emotions are expressed they are sometimes dismissed under the umbrella of ‘challenging behaviour’? Valerie Sinason, child psychotherapist and adult psychoanalyst specialising in learning disability, proposed a theory in the early 1990s called the “handicapped smile” (1992). This term refers to the habit of compliancy, happiness and smiling despite pain or negative emotions, in order to be accepted and maintain the status quo. This “outward sign of a psychic defence” (Lloyd, 2009, p.63) guards and disguises intense pain (for themselves and for others), “the body attempting to make a self-effacing apology for the mind within” (Fonagy, 1993, p.118). Whilst I am not convinced that this is necessarily the case, it was clear that as we looked at the role of the curator we also need to develop ideas of critical engagement. However with some support, everyone chose something that they would take out of the exhibition. It was here I identified something important in terms of my facilitation for this study. I learnt I needed to think carefully on how I frame critical questions to the group. Instead of asking the curators what they did not like and polarising their opinions automatically, I instead asked; 'which one would they edit out?' or 'which one doesn't work for what you're trying to say at the moment?' I took this approach forward to the next phase of the study when the curators are required to make selections or edits as 'liking' and 'disliking' are too simplistic for curating.

For the final activity of the day at Tate Liverpool we explored Matisse In Focus. The exhibition, curated by Tate Liverpool’s Assistant Curator Stephanie Straine, displayed Matisse's famous The Snail from his later cut out works for the first time in any UK gallery outside of London. I was surprised to see that The Snail (1953) was the only piece from his cut out series with the exhibition predominantly showcasing his bronze works and paintings. The group also picked up on this reflected in that they all chose to sketch The Snail and none of the other pieces. After an initial look around I asked the group to write or draw in their sketch books what they saw in the gallery other than the art work. I gave them the example of the Matisse catalogue found on a bench which was there so visitors could look at his other work, or perhaps be encouraged to buy it from the Tate’s shop. I asked the group to do this activity as I wanted to support them to take notice of what is included in an exhibition and reflect on why it is there. An exhibition usually contains more than just the artworks themselves and the group would have to think about what they wish to include in their own exhibit.

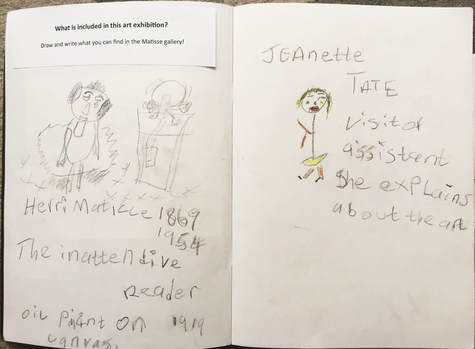

Diana's sketchbook activity

Diana's sketchbook activity

This activity yielded some interesting responses. Leah was one of the only curators to record textual items including artist statements and the main gallery text, most likely because she is the only group member who is able to read and write independently. Most of the group drew a picture of the 'Make it Station', a trolley of materials in which the audience are invited to make their own Matisse cut out. At the time the station was mobbed by children, and the group all really liked the idea of making in the gallery. We all commented on the injection of fun and energy it brought into the space, but for other gallery-goers it seemed an unwanted and distracting presence.

Diana had some fantastic observations and sketched the gallery invigilator whom she had been chatting to. Next to her drawing she wrote the invigilators name. When I asked Diana why she had included it she said 'the staff are important they can help you'. This opened up lots of conversation with the group about how they may incorporate staff such as training them and tours, particularly if you are unable to read. For the group, this impacted ideas of curating. Here we gained insight; curating is not just selecting and putting works on walls, it is entangled with the whole way the gallery works.

All of the group recorded that there was a projector playing a film in the gallery.

Diana had some fantastic observations and sketched the gallery invigilator whom she had been chatting to. Next to her drawing she wrote the invigilators name. When I asked Diana why she had included it she said 'the staff are important they can help you'. This opened up lots of conversation with the group about how they may incorporate staff such as training them and tours, particularly if you are unable to read. For the group, this impacted ideas of curating. Here we gained insight; curating is not just selecting and putting works on walls, it is entangled with the whole way the gallery works.

All of the group recorded that there was a projector playing a film in the gallery.

|

SCENE 2: THE FELLA WITH THE SCISSORS

At Tate Liverpool visiting the Matisse in Focus exhibition. The group are watching a video of Matisse creating his cut out artworks with an assistant. There is no audio to the black and white projection. JADE: So what do we think of the film then? HANNAH: Good, yeah I like it, yeah, I drew it! EDDIE: Yeah I like this, who’s the fella with the scissors then? JADE: It’s Henri Matisse. That’s whose exhibition it is and whose artwork is in the gallery. Can you see he’s making a similar piece to that one over there? [Jade points to The Snail artwork behind them] EDDIE: Oh yeah! Yeah I like this, it says a lot doesn’t it? LEAH: Is Matisse disabled? He looks like he’s getting help from that woman? JADE: Yeah towards the end of his life, I guess he was. EDDIE: I’d like one of these videos in our show. It just works doesn’t it? Tells you everything. |

This video[1] showed Matisse making his work and the scene above took place in response to it. The group were captivated. Eddie in particular raved about the use of film and wrote down in his sketch book that he would want something similar in his own exhibition. This scene was a pivotal moment for the curators and one that they frequently returned to in response to the question of interpretation and giving their own exhibition meaning and context for visitors. Throughout the project, they felt this was the most successful example of gallery interpretation they came across. Further discussion on interpretation in Act 4: Auto Agents.

During the course of this study Halton Speak Out began increasingly using film. In 2014 Halton Speak Out’s performing arts group Ella Together collaborated on a film titled We Are People Too. This short film, based on a poem written by Leah of the same name, features writing, acting, directing and filming by self-advocates. It follows a young woman over the course of an ordinary day experiencing discrimination and bullying for being ‘different’. In this film the protagonist appears not to have a disability, whilst the rest of the cast does. Here the majority/minority is flipped placing the self-advocates in an empowering position and as Leah describes, “being the ones doing the staring and not being stared at for a change”. Halton Speak Out consider film a medium which is more accessible than easy read reports, as it does not rely on an individual’s ability to read or write. The use of film within Inclusive Arts has also grown considerably, reflected in the success of Oska Bright Film Festival run annually by Carousel since 2004, as well as becoming more commonplace in research. An early case study on the adoption of film into research is titled Plain Facts which was funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and was in circulation for over ten years, between 1995 and 2007. Plain Facts aimed to provide accessible research summaries for people with learning disabilities and two researchers in particular, Ruth Towson and Julian Goodwin at the Norah Fry research centre, considered the use of film. Goodwin who identifies with having a learning disability reflected:

|

I think that using film is something that we will keep doing in getting information to people with learning disabilities. I think that the films need to be on YouTube so people with learning disabilities can find them easily. People do have computers but they only use the websites they know, to find things. (2015, p.98) |

However, the use of film to capture people's 'voices' to me implies that film is capable of capturing an authentic representation, but my professional background in photography leaves me sceptical about this. Films relationship to portraying 'reality' is strained and to me it more accurately straddles “fact and fiction, art and document, entertainment and knowledge” (2004, p.73). Just like other visual art forms, film is constructed, framed and edited by the film maker and as photographer.

The second visit I shall discuss took place on the 22nd February 2016, four weeks after Tate Liverpool, to Museum of Liverpool. Having opened in 2011 replacing the former Museum of Liverpool Life, the purpose of the museum if to tell the story of Liverpool and its people, and reflect the city’s “global significance” (Museum of Liverpool, 2017). Whilst not housing much contemporary art, I felt it was important for the group to visit as it is regarded as a key space in Liverpool for art and culture. Museum of Liverpool also presents an opportunity to experience and discuss multi-sensory exhibitions which in my experience, museums tend to be more so than galleries. And to visit The People’s Republic, an exhibition all about people from Liverpool with a focus on social change.

Hannah in the kimono at MoL, 2016

Hannah in the kimono at MoL, 2016

In the morning of the visit, we explored the downstairs galleries which includes The Global City and The Great Port. These galleries place a focus on Liverpool’s historic past as a key port in Europe with many historical objects, photographs, recreated objects and some art works. There are many cases, projected films, and interactive objects for visitors. I asked the group to explore these spaces and find three different types of sensory objects; something they could touch, smell and wear. This exercise was intended to support the group to take notice more closely of what is around them and to record types of engagement we have not previously encountered at galleries. All of the group noticed how differently the Museum of Liverpool was curated in comparison to the Tate Liverpool and Walker Art Gallery, “it’s much busier and full” commented Eddie, “there’s stuff everywhere” – a stark comparison to Tate Liverpool’s bright white walls and minimal display approach. Leah and Hannah really enjoyed the interactive aspects of the museum, particularly dressing up in the Kimono’s found in the China Town section (with Hannah even acting in her costume!).

Leah said it reminded her of being at Ella and that “getting involved is always more fun”. Everyone managed to find items from my list in the galleries but Tony did comment that he felt like “it’s for kids”. I’m not sure whether that was because there were lots of kids on a school trip in the gallery or that he felt that the interactive nature was more aimed at children. How much audience interaction would be present in their own exhibition was debated by the group. As we can see from this example, some felt that more interaction the better, however others felt it might be too childlike or deemed as not serious. For their own exhibition, the group worked with the artists to negotiate the level of engagement, and the conversation changed. It became less about how much or how little, and more about how does interaction help the audience connect with the ideas?

Leah said it reminded her of being at Ella and that “getting involved is always more fun”. Everyone managed to find items from my list in the galleries but Tony did comment that he felt like “it’s for kids”. I’m not sure whether that was because there were lots of kids on a school trip in the gallery or that he felt that the interactive nature was more aimed at children. How much audience interaction would be present in their own exhibition was debated by the group. As we can see from this example, some felt that more interaction the better, however others felt it might be too childlike or deemed as not serious. For their own exhibition, the group worked with the artists to negotiate the level of engagement, and the conversation changed. It became less about how much or how little, and more about how does interaction help the audience connect with the ideas?

In the afternoon we headed to The People’s Republic. The group seemed to really enjoy this space; the mix of old historic pieces such as the women’s suffrage case and newer creative pieces like the Liverpool Map (an artistic glass map created for Liverpool Biennial 2008). After an initial look around, I asked the group to find a piece which they “felt told an important story”. With this activity plan, I was trying to get the group to look beyond the visual appeal of the items to consider that the items represented. In the exhibition many different stories were told from unemployment, wartime Liverpool, Liverpool’s changing housing, Gay pride in Liverpool, the historic architecture and the famous scouse accent.

Exploring Court Housing, 2016

Exploring Court Housing, 2016

All the group spent a lot of time in Court Housing. This installation aims to enable visitors to “experience life in 26 Court, Burlington Street, North Liverpool in 1870”. This is in the Scotland Road area, one of the most overcrowded and neglected parts of Victorian Liverpool. Small houses built off dark, narrow courtyards provided cheap housing for the huge numbers of people moving to the city at the time. This was a really memorable piece for the group as they all spent quite some time in it sketching. There were soundscapes within the space which brought to life residents stories which were very popular with the group. It was also memorable as they all found the privy (and toilet related noises) totally hilarious! Lots of conversations ensued how the curator of this installation managed to make it fun even though it was dealing with the “sad” topic of poor housing conditions which people had to live through. Is it appropriate, we asked, to make light of a serious subject? Or is the fun element doing a great job of engaging people? This was a great example, and one I returned to throughout the project, to discuss how a curator’s decision can be interpreted differently by different people. Some could find the toilet humour funny, others could find it distasteful.

Leah found this exercise particularly enjoyable and was quick to look around and pick her piece. She chose the women’s poppy memorial, a small found room in the gallery with the walls decorated with veterans’ names, medals and a sound scape. Leah spent a long time listening to the pieces and was able to describe the narratives to me. She felt like “the curator has made it of people’s experiences of their family’s pasts about those who were in wars/RAF fighting for their lives. I am passionate about the connection to this story as my poppa used to fly in the RAF…”. Myself and Leah also talked about the bespoke structure the curator had designed. She felt like it had been made as a place to retreat to reflect. Leah also commented that the idea of “important stories” is not new to her and is often used in her self-advocacy work. Often she has helped people “record their important stories” and I vividly remember in my first year of this study Leah sharing her own life story book with me.

Leah found this exercise particularly enjoyable and was quick to look around and pick her piece. She chose the women’s poppy memorial, a small found room in the gallery with the walls decorated with veterans’ names, medals and a sound scape. Leah spent a long time listening to the pieces and was able to describe the narratives to me. She felt like “the curator has made it of people’s experiences of their family’s pasts about those who were in wars/RAF fighting for their lives. I am passionate about the connection to this story as my poppa used to fly in the RAF…”. Myself and Leah also talked about the bespoke structure the curator had designed. She felt like it had been made as a place to retreat to reflect. Leah also commented that the idea of “important stories” is not new to her and is often used in her self-advocacy work. Often she has helped people “record their important stories” and I vividly remember in my first year of this study Leah sharing her own life story book with me.

|

Life story is a tool which has been adopted in self-advocacy practices (Atkinson 1997; Hewitt 1998, 2000), but has also played an important part in the emergent methodologies of inclusive and participatory research (Goodley 1996; Goodley, Lawtham, Clough and Moore, 2004). As Helen Hewitt suggests, there is no right or wrong way to compile a life story book, which only “emphasises their individual nature” (2003, p. 22). They can be a simple poster with photos that are important to the person, a scrap book that is continually added to or computerised document. It is thought life story books originated in social services settings for use with children who were being placed for adoption and fostering (Ryan and Walker, 1985, 1993), but since then they have been increasingly used with people with learning disabilities (Bogdan and Taylor 1982; Walmsley 1995; Atkinson 1997; Hewitt 1998), particularly in care settings during transitions like changing accommodation, as there is a risk that the stories and experiences a person has had, could get lost (Ledger, 2012). This is especially true if staff who have known the person for a number of years do not move with them. During my years as a support worker for Mencap, many of my warmest memories about my job are about people showing me their life story books. They enable you very quickly to see what is important to that person and as Hewitt (1998) suggests, they encourage people to see that person as an individual, moving beyond the parameters of care plans, where the information about the person is limited to that of a clinical nature and are very future-orientated, meaning there is a considerable risk that “the past is filtered out” (Moya, 2009, p.136). Some researchers and practitioners also propose that life story books are not just a biographical account, but also a tool for self-advocacy (Meininger, 2006). Hreinsdóttir et al. propose that the telling of a life story is “in itself, an important act of ‘speaking up’” as it gives a voice to a previously silenced and excluded group (2006, p. 159).

|

reflecting on visits together

Back at Bluecoat, we began reflecting on our gallery and museum visits by making zines. Zines (pronounced 'zeens') can be classified as self-published, low-budget, non-profit DIY (do-it-yourself) print publications. There are no hard and fast rules to what a zine should look like, but they mostly are photocopied or uniquely printed booklets, stapled or bound in a creative way, featuring text (typed or handwritten) and images (photos, cut and paste, drawings). As well as looking very different, the content and subject of zines also varies hugely. Originally zines were born out of fandom; particularly sci-fi, music, sport and reworking’s of pop culture iconography. In the 1970’s punk zines became very popular in response to the rising popularity of the punk music scene, however often these excluded the voices of women and ethnic minorities. Thus a wave of zines emerged in the 1980’s and 1990’s around feminism, racism and “all variety of personal and political narratives” (Piepmeier, 2008, p.214). Once created, zines are distributed in various ways. Sometimes zines are created and distributed with a small niche community of existing friends and other zinesters, other times they circulate in and beyond their original communities and can be traded or sold via zine distributors (known as distros), at zine fairs, record shops and also found in community spaces such as libraries. With no regular copy schedule, subscription list, international book numbers, or professional print jobs, most cut-and-paste zines circulate through informal distribution networks, which for me, highlights not just the materiality of the object, but its unusual audience.

The choice to make zines with the group was primarily due to their flexible physical format. As zines are so visually diverse I felt that this opened up a wide scope of expression which could include text, images (both sketched and found), ephemera and mark making. However, in addition to the way they look, I am also interested in how zines speak to issues of inclusion and exclusion; key issues in both museological and self-advocacy contexts. On the one, hand zines can be seen as incredibly inclusive in that anyone can make one with no real skill, specialist equipment or training. But on the other hand, zines can be viewed as exclusionary in that often they are made with the intention to be distributed amongst a very specific niche audience with little regard to attracting an ‘outside’ readership. Whilst this is useful in challenging notions of what ‘knowing’ might be and who gets to determine its legitimacy (as appose to more formal publishing routes which require an institutional review and approval of some kind), zine makers run the risk of limiting the social or political work their zines could achieve through intentionally excluding the majority. Janice Radway suggests a zine makers validation comes with not only finding an audience, but also “pursuing actual connections with those who read their zines, wrote back, and offered their own zines in exchange” (2011, p.147). I believe this relationship also is evident in self-advocacy. Self-advocacy writer Anne Marie’s claims, “there are two parties to making self-advocacy work: people with intellectual disability speaking out and other people listening to what they have to say” (Callus, 2013, p.1), emphasising the importance for expression not just to made, but to be acknowledged. It strikes me that what zine makers and self-advocates appear to have in common is the desire to communicate their work to specific audiences. Whether a zinester reaching out to fellow feminists, or a self-advocate reaching out to care providers, both aim to spark dialogue with a targeted group.

The choice to make zines with the group was primarily due to their flexible physical format. As zines are so visually diverse I felt that this opened up a wide scope of expression which could include text, images (both sketched and found), ephemera and mark making. However, in addition to the way they look, I am also interested in how zines speak to issues of inclusion and exclusion; key issues in both museological and self-advocacy contexts. On the one, hand zines can be seen as incredibly inclusive in that anyone can make one with no real skill, specialist equipment or training. But on the other hand, zines can be viewed as exclusionary in that often they are made with the intention to be distributed amongst a very specific niche audience with little regard to attracting an ‘outside’ readership. Whilst this is useful in challenging notions of what ‘knowing’ might be and who gets to determine its legitimacy (as appose to more formal publishing routes which require an institutional review and approval of some kind), zine makers run the risk of limiting the social or political work their zines could achieve through intentionally excluding the majority. Janice Radway suggests a zine makers validation comes with not only finding an audience, but also “pursuing actual connections with those who read their zines, wrote back, and offered their own zines in exchange” (2011, p.147). I believe this relationship also is evident in self-advocacy. Self-advocacy writer Anne Marie’s claims, “there are two parties to making self-advocacy work: people with intellectual disability speaking out and other people listening to what they have to say” (Callus, 2013, p.1), emphasising the importance for expression not just to made, but to be acknowledged. It strikes me that what zine makers and self-advocates appear to have in common is the desire to communicate their work to specific audiences. Whether a zinester reaching out to fellow feminists, or a self-advocate reaching out to care providers, both aim to spark dialogue with a targeted group.

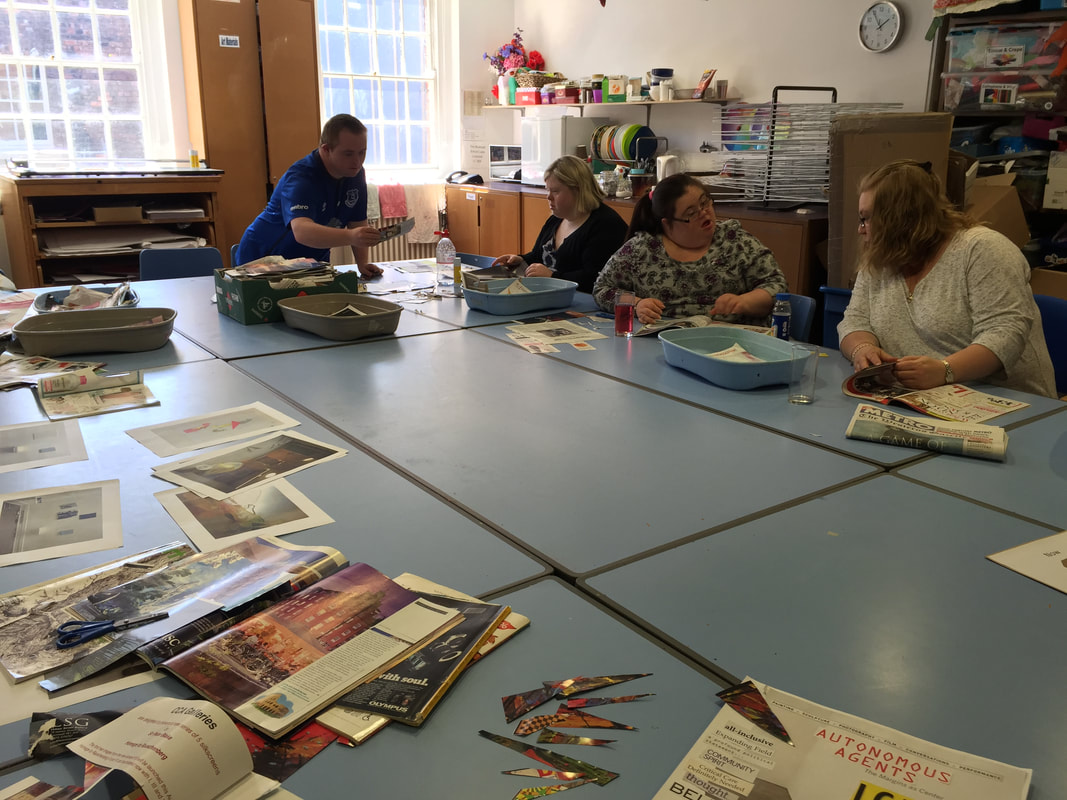

In our first reflective workshop I showed the group a selection of zines from my personal collection. Many of the zines I have collected over the years feature artist zines, feminist zines as well as some disability themed zines. The group were amazed by the sheer variety and were all enthusiastic and curious about who had made them. I decided to use this particular reflective workshop to do a check back with the group, going over some old ground to see what they remembered and what was resonating from recent gallery and museum visits. I asked them to think about ‘what’s inside an art exhibition’, based on the activity we had done together in Tate Liverpool. With little prompting the group came up with ideas; staff, artwork, information, and with the help of their sketchbooks, they were able to contribute more. We wrote down these ideas and from them created a zine. The group approached this task by selecting an idea such as ‘gallery staff’, and then searched through old newspapers and magazines to find images or words they felt corresponded with it. What is worth noting about zining using this traditional cut and paste method is that often what you create is very much shaped by the materials in front of you at that time. Once pictures and words were collected, they began arranging and editing them on a page.

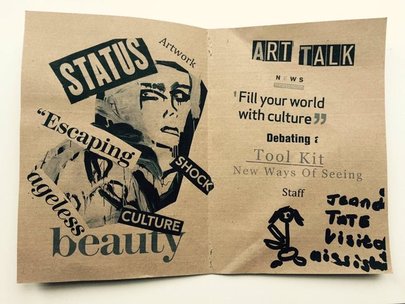

Leah's zine 'status' zine page (left)

Leah's zine 'status' zine page (left)

Leah's first zine page (left) was particularly striking. In response to the zines topic of 'what’s inside an art exhibition', Leah made a page around 'artwork' for which she selected an image of painted women and the word 'status' as mentioned in Act 1: The Prologue. This immediately caught my attention as ‘status’ is not a word I have heard or seen Leah use before. I asked Leah why she chose to include the word status and she said “it means you're important”. I was intrigued to know in what context she had encountered ‘status’, perhaps it was her role as a self-advocate? Apparently not. Leah had heard it “on TV somewhere”. Here I am reminded of the power of TV and stories, demonstrating the role of storytelling as a crucial meaning making device for this project.

|

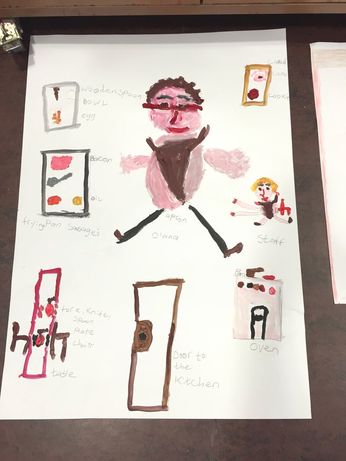

After lunch, we focused on thinking about our visit to the Museum of Liverpool. The group discussed their most memorable moments which centred around the The People’s Republic and in particular the Court Housing installation. In response to this piece I asked the group to think about their own housing and living, and to tell a story by creating a picture. Alongside their picture like the Court Housing installation, they could also create a soundscape of themselves describing their picture and ‘telling their story’. This activity really captivated the group and everyone was energized by the idea of combining both sound and images which for me was quite telling. Later in the project when we progressed to using moving image and sound to develop interpretation, I was confident that the approach engaged the group and it reflected their interests. I feel it is important to mention however that the group did not always respond as enthusiastically to all activities. Whilst always professional and obliging during the project, now and again their reaction would be lukewarm or someone would ask; “can we do something else now?”. Comments like these were crucial markers for me. Just as when I noticed specific techniques resonated with the group – like combining images and sounds – it was equally important for me to gauge when an approach was less successful. This supported me to refine the ways in which to work with the group, and later, in facilitating the artists to effectively work with them too, which was important given the limited time frame of their collaboration.

|

Leah making her 'independence' artwork, 2016

Leah making her 'independence' artwork, 2016

During this activity, the group all produced very different work. Diana created a piece (above) which almost resembled story book throughout her life – all of the different places she’d lived and the good and bad support she had received. Diana told the story of her multiple housing situation and how in care she was made to live in many places as a child from 'with the nuns' to a 'sort of boarding school which I didn't like'. With her image which is a collage of small pictures, words and descriptions she made a sound recording.

Leah produced a drawing depicting what she recognises as the biggest shift in her living situation; moving from her home in Widnes, where she grew up, to her current home in Runcorn. On one side the page Leah drew her friends and family in Widnes and on the other, her family home in Runcorn and separating the two is the Runcorn Widnes bridge. “I have a social P.A now who helps me go back to Widnes and catch up with people” Leah explained, “he knows all the same people as me you see”. It was interesting to learn that Leah specifically employs somebody to support her to stay connected to people in her past, as often we do not think a support worker in these contexts. We think of support workers as somebody to assist with everyday tasks of living “an ordinary life” (Windley and Chapman, 2010, p.38), but this connection surely supports Leah’s pursuit of a ‘good life’? (Johnson, Walmsley and Wolfe, 2010).

Leah produced a drawing depicting what she recognises as the biggest shift in her living situation; moving from her home in Widnes, where she grew up, to her current home in Runcorn. On one side the page Leah drew her friends and family in Widnes and on the other, her family home in Runcorn and separating the two is the Runcorn Widnes bridge. “I have a social P.A now who helps me go back to Widnes and catch up with people” Leah explained, “he knows all the same people as me you see”. It was interesting to learn that Leah specifically employs somebody to support her to stay connected to people in her past, as often we do not think a support worker in these contexts. We think of support workers as somebody to assist with everyday tasks of living “an ordinary life” (Windley and Chapman, 2010, p.38), but this connection surely supports Leah’s pursuit of a ‘good life’? (Johnson, Walmsley and Wolfe, 2010).

an exhibition theme emerges...

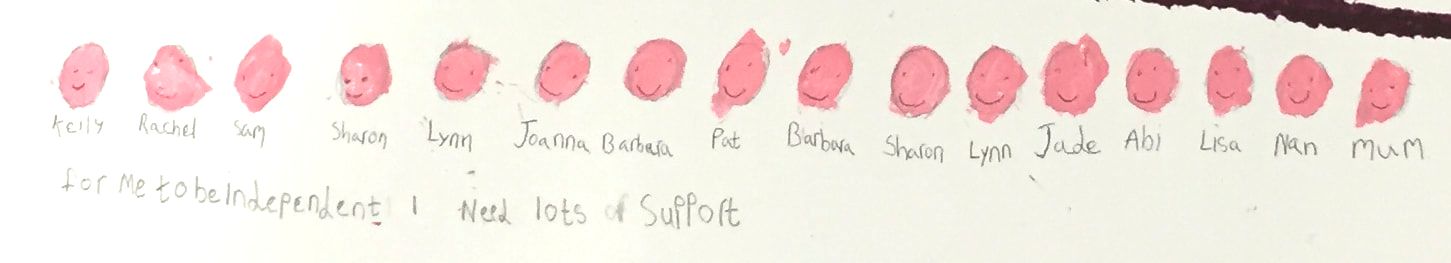

After nearly three months of visiting galleries and museums, what was emerging was an interest in exhibitions or displays that related to personal stories or histories. In previous weeks we had been exploring the groups housing experiences based on the Court Housing installation at the Museum of Liverpool, and the group conversations coalesced around issues of independent living and levels of support. Building on this interest, I asked the group to make an artwork based on the word ‘independence’. This idea came from a previous discussion around support and different types of support experienced by the group. I advised the group they could imagine that word in any way they wanted through any material in the studio.

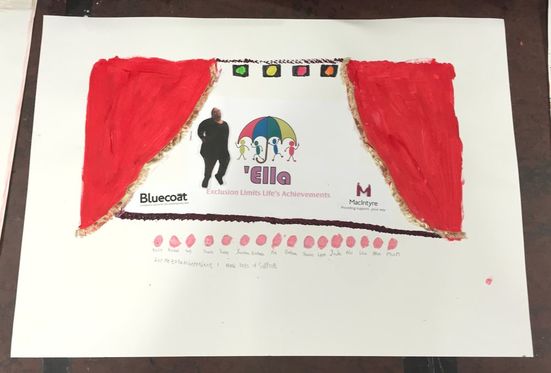

Hannah's 'independence' artwork

Hannah's 'independence' artwork

Hannah created a large-scale mixed media image of a stage with herself on it. The stage is adorned with theatrical plush red velvet curtains and the Ella Together logo (Halton Speak Out’s performing arts group of which she is a member) which she printed and carefully cut out. Underneath the stage, seemingly propping it up, are the names of all the people it takes for Hannah to be a performer in Ella Together. Discussing the piece with Hannah and her supporter Donna, Hannah feels that Ella is a place where she feels truly independent, however as Donna points out, it is also an area in Hannah’s life where she requires many layers of support to make that happen. From her family providing transport each week, to financial support to pay the membership fees, to a one to one support worker to learn dance routines, stage directions and scripts, to the volunteers and the teachers at Ella Together; many people are involved to ensure Hannah has those feelings and experiences of independence. I feel Hannah’s artwork provides a great visual example of the interdependency model of disability discussed in The Prologue. Independence is not always about barrier removal but enabling complex networks, which we all need. This image would become a useful tool in which to discuss and reflect on the network of support around the group as curators later in the project.

Tony created an artwork which resembled a map. It detailed places around Liverpool which held great importance to him - Bluecoat, his home, Goodison Park, the Albert Dock, his local pub – and weaved between the various buildings was himself alone in buses, taxis and holding a key. Tony explained how taxis were a recent addition to his life and very important to him as they have enabled him to come and go as he pleases. He also was learning to use a bus on his own and had recently been given his own house key to further support his independence which he was very excited about. For Tony, I sense that independence was underpinned by feelings of freedom which for him translated to freedom of movement at this particular time in his life.

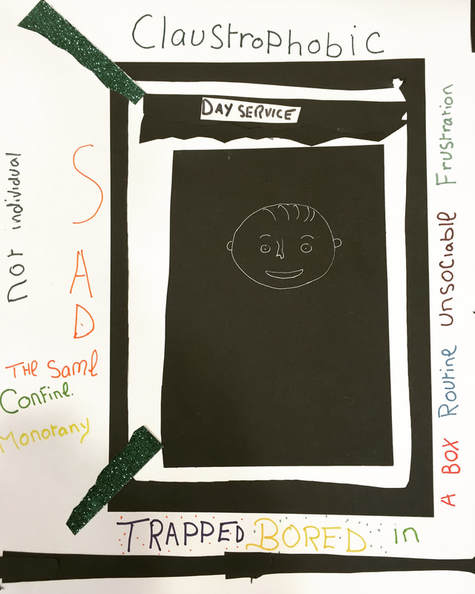

Eddie's 'independence' artwork

Eddie's 'independence' artwork

EEddie’s approach to the task was different. Instead of creating an artwork which celebrated feelings and examples of independence, his depicted a time in his life where he felt he had none. As an older man, Eddie spent many years in day services. “You did the same thing everyday” he explained, “you couldn’t go nowhere, and you’re not in it [referring to city centre] you’re just stuck away”. Eddie created an image which portrayed himself “trapped” in the day service system. In the centre of a black box, is a simple white line drawing of himself which seems to peer out of the darkness. Surrounding this is a black frame labelled ‘day service’, which perhaps represents a building. Around the edges of the image are handwritten words in different colours which read; “claustrophobic”, “frustration”, “a box”, “unsociable”, “sad”, “not individual”, “confine”, “trapped”, “bored”, “the same” and the list goes on. Eddie began with the words trapped and bored and used the computer to research words to expand the piece. The younger members of the group; Hannah and Tony were upset by the piece, as was Donna and Abi. This piece reveals how the social aspect of Bluecoat is incredibly important to Eddie. In February 2017 to celebrate the buildings 300th birthday, Bluecoat exhibited Art at the Heart of Bluecoat. This exhibition explored the central role of art at Bluecoat which started over a century ago, through key personalities, exhibitions and organisations that found a home in the building. Eddie is one of the ‘key personalities’ featured in this exhibition via a video The Eddie Rauer Spectacular. In the video interview Eddie discusses how many friends and acquaintances he has at Bluecoat and how they have fed into him leading a happier more independent life.

In the afternoon of this workshop I decided to change the planned activity, which was going to be around brainstorming in a more formal way for the exhibition theme. Instead, responding to the changed energy in the room after difficult discussions around Eddie’s past, I asked them instead to collage as a group some ideas for the exhibition theme. This was intended to move away from oral discussions which the group seemed weary with, into a task which was more about making.

In truth, I wasn’t entirely sure how this would pan out. I first told the group they had 20 minutes to look through all of the materials (flyers, magazines, newspapers, etc) and collect pictures, patterns, words that they thought suited the exhibition theme. By the end of the 20 minutes, there was a lot of stuff on the table. Too much. So I asked the group to take turns editing it down, which is a really useful skill to practice as curators. “Do we have any which are the same?”, “Are there any you wish to take out”, “Are there any that confuse you?”, were questions I asked to support the editing process. I then put the group into pairs and asked them to find their favourite pieces of material. I noticed there were some obvious favourites and some arguing began to happen on what would be included. I tried to frame this as a good thing – this material really works! Let’s not argue but put it in the yes pile. This brief exercise flagged up that when we come to making bigger decisions, I need to think carefully on how to frame questions and what to do when there is a disagreement.

In truth, I wasn’t entirely sure how this would pan out. I first told the group they had 20 minutes to look through all of the materials (flyers, magazines, newspapers, etc) and collect pictures, patterns, words that they thought suited the exhibition theme. By the end of the 20 minutes, there was a lot of stuff on the table. Too much. So I asked the group to take turns editing it down, which is a really useful skill to practice as curators. “Do we have any which are the same?”, “Are there any you wish to take out”, “Are there any that confuse you?”, were questions I asked to support the editing process. I then put the group into pairs and asked them to find their favourite pieces of material. I noticed there were some obvious favourites and some arguing began to happen on what would be included. I tried to frame this as a good thing – this material really works! Let’s not argue but put it in the yes pile. This brief exercise flagged up that when we come to making bigger decisions, I need to think carefully on how to frame questions and what to do when there is a disagreement.

Another issue that the collaging activity flagged was around text. It found it surprising how many words the group wanted to include despite their difficulties in reading, which I suspected may be because they struggled to think what independence could look like pictorially. Although the group had so far expressed that they wanted to do an exhibition about independence, to me, many of their conversations about independence actually circled around notions of autonomy. ‘Being your own boss’, ‘making your own decisions’, ‘deciding what’s best for you’, speaks directly to issues of self-governance. Autonomy and independence can be considered as synonymous on one level, although there is a subtle difference between the two words. With the term ‘autonomy’, the main focus is on individual power. With the term ‘independence’, the main focus is on not being dependent or influenced. Autonomy focuses on the ‘self’ which is also reflected in the terms etymology from the Latin ‘autos’. As we have seen in the literature discussed in Act 1: Prologue, the concept of autonomy is contested both in the context of self-advocacy, and in the context of curating and art making. However, I was faced with a dilemma. Do I as a facilitator introduce the group to new words in an attempt to broaden their self expression? Or is that putting words in their mouths? And, does it really matter what word is used? Or will their choices of words have a direct affect the type of artists selected and artwork developed for exhibition? However, an answer emerged.

|

SCENE 3: IT’S FATE! THAT FUNNY WORD AGAIN…

During a group collaging exercise, Donna has an interesting find in one of the magazines and shares it with the group. DONNA: [Laughs] Guess what I’ve found DIANA: What, what? DONNA: That word Jade was talking about before EDDIE: What’s that? DONNA: Remember that funny word Jade was talking about before? Autonomy? Look what was in my magazine! [Donna shows the group a cut out of a title ‘Autonomous Agents’, taken from an article about robots]. EDDIE: Oh yeah! Look at that! DIANA: Oh my god! ABI: That’s so cool! EDDIE: [Sings] It’s meant to be! LEAH: It’s fate! We need to put that in the yes pile HANNAH: [Claps and laughs] |

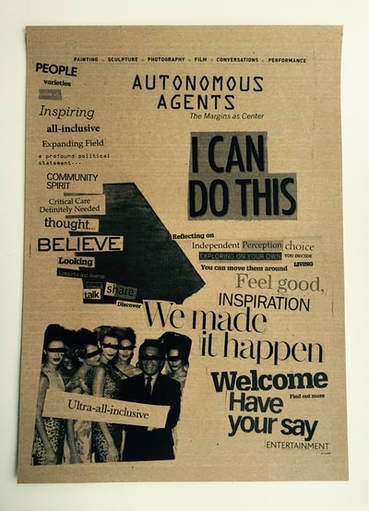

'Autonomous Agents' completed collage

'Autonomous Agents' completed collage

In this scene we see the emergence of the groups exhibition title. The ‘autonomous agents’ clipping was found by Donna in a lifestyle magazine as part of an article about the use of robots in the future. Donna, who had also never heard of the word autonomy before our discussion that day, was surprised to find the word in a lifestyle magazine. The group really liked the serendipity factor of the clipping and they all agreed that it should be the title of the collage, and intriguingly placed it at the top of the piece, even though the majority of the other words clustered at the side of the page. “Could this the name of the exhibition?” I asked, “It looks very important as it’s at the top of the page?”. “I think it’s a good exhibition name” replied Leah, “autot-y-nomis agents, or however you say it”. “Yeah I like that one” replied Diana, “thingy agents”. I could see an issue emerging; the group had difficulty pronouncing ‘autonomous’ and some members refused to say it all together. “Is it a good idea to call your exhibition something we struggle saying?” I enquired. “That’s a good point” said Eddie, “We don’t want to look stupid” he said with a laugh. I felt this was a conscious effort on Eddie’s behalf to bring to the surface the ‘elephant in the room’, their learning disabilities and the stigma that is attached to it. Eddie’s perceived risk of ‘looking stupid’ was of particular concern to him throughout the project. He seemed more aware than others in the group that his exhibition would be viewed and ‘judged’ by not just visitors, but people he knew. For me it was clear that the group understood the meaning of the word autonomous, there was simply difficulties in pronouncing it which was causing some awkwardness. In self-advocacy contexts simplifying both spoken and written language through “plain language, the use of keywords, short words and sentences” is key concept for promoting access for learning disabled people (Godsell and Scarborough, 2006, p.64). “If you find it a mouthful, then we could just shorten it?” I suggested, “How about Auto Agents?”. “Yes I like that!” said Tony, “better”.

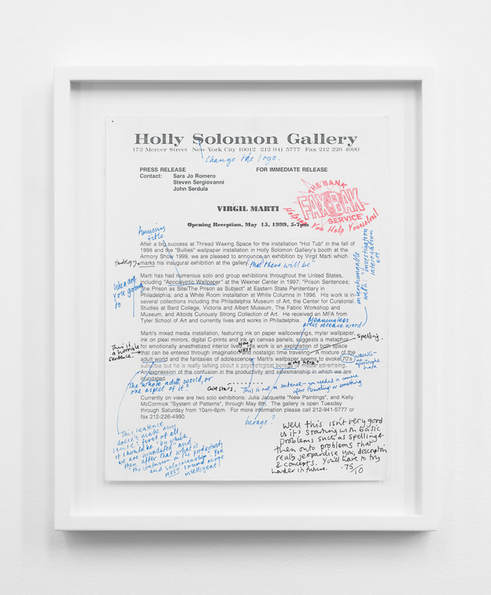

BANK, Fax-Bak (NY:Holly Soloman), 1999

BANK, Fax-Bak (NY:Holly Soloman), 1999

The arts, however, have appeared reluctant to embrace the same approach to using simple accessible language. Galleries have been accused on disguising information in overly complicated, specialist art languages. In 2012 an essay entitled International Art English by David Levine and Alix Rule attempted to scientifically prove that the “The internationalized art world relies on a unique language… This language has everything to do with English, but it is emphatically not English”. Here they identified a language subsequently dubbed ‘artspeak’ which, is littered with “pompous paradoxes” and “plagues of adverbs”, and mainly serves “as ammunition for those who still insist contemporary art is a fraud” (Beckett, 2013). One of their conclusions is that International Art English is used by its proponents to both identify each other and signal their insider status and authority within the art elite. But, this pervading artspeak phenomenon has long been critiqued by artists. The Fax-Bak project by BANK (Simon Bedwell, Milly Thompson and John Russell) saw gallery press releases returned to galleries with corrections and commentary, and have since become BANK's best known work. They corrected the grammar, critiqued the logos and typefaces in use, deconstructed the text to highlight the many examples of pretentiousness, meaningless assertions and general misuse of the English language on display in galleries. They always gave texts marks out of ten and faxed them back to the galleries from which they came. And then they exhibited them, seemingly making an example of the absurdity of artspeak.

During May 2016 Marie-Anne McQuay, Bluecoat’s Head of Programmes, wrote to the Bluecoat team in order to begin the process of putting together the Autumn 2016 brochure, which would cover September, October and November that year. Marie-Anne anticipated that Bluecoat’s programming team would be particularly busy during the summer period, due to their involvement with Liverpool Biennial, and suggested that the Autumn brochure should be planned further in advance with earlier deadlines. As the groups exhibition fell at the very end of the Autumn brochure, this meant the group was now under pressure to produce a public facing text much earlier than we would have liked. To put in context, when asked to produce copy and an image for the brochure, we had not yet selected any artists and had yet to hear about any funding. Still, the group had to press on with putting together text to attract visitors to the show. Here we experienced how institutional frameworks and deadlines of the gallery also shape the work of a curator. Would the group have gone with Auto Agents as their exhibition title/theme if the deadline was not looming?

I approached the group on how we should approach producing writing for the brochure. Not all members of the group can read or write so they nominated Leah and she agreed to take the lead in writing and overseeing the text. To do this, Leah emailed Marie-Anne to ask for important to include in the copy. Marie-Anne came back to Leah with the following pointers; “100 words is basically the essential information: What is the show called? Who is in it? What is the theme of the show? Who has curated it?”. From this Leah wrote the first draft which was then workshopped with Halton Speak Out self-advocates and Blue Room members for feedback. The group felt it was really important for the text to as accessible as possible, so they felt a good way to test it out was by asking the opinion of lots of people who have a learning disability in their peer groups. The workshops proved that some words were confusing – ‘commission’, ‘collaboration’ and ‘autonomous’ were flagged by both groups as difficult. Leah decided to take out these words completely and replace them with new words such as ‘new art’, ‘working together’ and ‘making decisions for yourself’. As no artworks had yet been selected for the show, the group decided to include a developed version of their group collage from which their exhibition title emerged.

The development of this text also threw up an important decision for the group; did they want audiences to know that the exhibition was curated by people with learning disabilities? Or, would they prefer not to disclose their learning disability at all? Throughout my own practice the issue of labelling has always been carefully reflected upon with my collaborators; the curators needed to make their own decision on how to label themselves within the context of the exhibition. I approached this topic with the group and framed it as; “what will be gained or lost by people not know you have a learning disability?”.

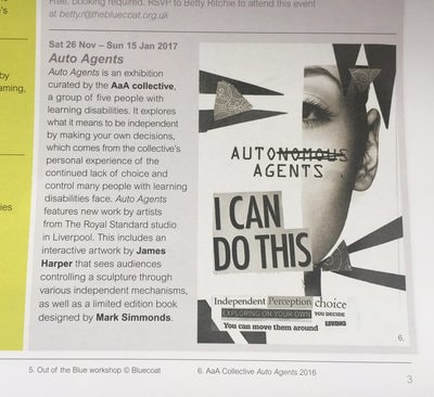

Close up of brochure

Close up of brochure

Eddie and Tony firmly believed that people did not need to know about their disability, and Eddie found it uncomfortable and even embarrassing to “have it out there”. Tony was incredibly invasive about his feelings around this topic other than that he didn’t feel it was necessary. I sensed Tony did not really identify with his learning disability label, often seeing himself as ‘different’ to others within his peer groups. In complete contrast, Leah was very passionate about alerting audiences to their learning disability status which was clearly informed by her background in self-advocacy. “If we don’t tell people, then we can’t change people’s minds about we can achieve” she explained. Unlike Eddie and Tony, it appeared that Leah found the use of the label empowering and saw the opportunities for change in doing so. Hannah also very clear that “it was a good thing” and explained how in Ella Together they “tell people at the shows all the time”.

The purpose and use of labels is complicated both in self-advocacy and art gallery contexts. For people labelled as learning disabled, the very label is just one in a long succession of descriptors applied to those people in our society who are categorised by a “matrix of psycho-medical assessments, marginalized by compromised intellectual function, characterized by increased health needs and excluded from the mainstream on the basis of reduced social opportunity” (McClimens, 2007, p.257). Self-advocates have long campaigned to have the terminology used to describe them changed and crucially, the right to self-define (Whittaker, 1996; Simons, 1993). For example, People First London have carried out service evaluations which they have published, participate in staff training and campaigned, with partial success, “to get the largest charity in Britain for people with learning disabilities (MENCAP) to change its image” and terminology (Finlay and Lyons, 2010, p.39).

For artists and curators, it also raises the issues surrounding how and/or when is it acceptable to label artwork produced by or in conjunction with a person with a learning disability? In Act 1: Prologue, I outline the key debates in regards to labelling which in summary highlights that labels can work to differentiate groups, and in doing so they can stigmatize. However, by excluding the artists label of learning disability, as Leah points out, do we perhaps miss the political work their art may achieve?

The purpose and use of labels is complicated both in self-advocacy and art gallery contexts. For people labelled as learning disabled, the very label is just one in a long succession of descriptors applied to those people in our society who are categorised by a “matrix of psycho-medical assessments, marginalized by compromised intellectual function, characterized by increased health needs and excluded from the mainstream on the basis of reduced social opportunity” (McClimens, 2007, p.257). Self-advocates have long campaigned to have the terminology used to describe them changed and crucially, the right to self-define (Whittaker, 1996; Simons, 1993). For example, People First London have carried out service evaluations which they have published, participate in staff training and campaigned, with partial success, “to get the largest charity in Britain for people with learning disabilities (MENCAP) to change its image” and terminology (Finlay and Lyons, 2010, p.39).

For artists and curators, it also raises the issues surrounding how and/or when is it acceptable to label artwork produced by or in conjunction with a person with a learning disability? In Act 1: Prologue, I outline the key debates in regards to labelling which in summary highlights that labels can work to differentiate groups, and in doing so they can stigmatize. However, by excluding the artists label of learning disability, as Leah points out, do we perhaps miss the political work their art may achieve?

After much deliberation, the group decided that it was important for audiences to know about their learning disabilities since their exhibition theme had emerged directly from complicated experiences of autonomy and support as learning disabled people. However, they wanted this not to be “in yer’ face” and “written on walls” but weaved subtly into the context. As the project progressed this would prove difficult as Bluecoat went onto include Auto Agents in a “season of inclusive arts at Bluecoat” alongside other learning disability led projects, which directly put the exhibition in the context of learning disability. For the programming team, this gave a prominent theme to organisation’s schedule which is helpful in terms of audience targeting, marketing and ticket sales. But it also meant that the project had been unable to shake off the framework of ‘inclusion’ often based around learning disabled people’s artwork. I wondered how, and if at all, Bluecoat consults members of Blue Room and their other learning disability projects on how they are labelled and presented to audiences.

Now a theme had been developed, the group needed artists…

Now a theme had been developed, the group needed artists…