A c t 4 A u t o A g e n t s

As the artworks were now firmly in development and nearing completion, the group began working more closely on developing interpretation, as well as organising a programme of engagement events and marketing materials. This final phase in the project made visible the curator’s role as a mediator situated within a large network and for me, the links between a self-advocate and curator were becoming more apparent. Just as self-advocates are required to operate within complex networks of support, I began to see how curators were also required to move and communicate between large networks, which now included not just the artists, but also Bluecoat’s programming team, front of house, marketing, press and the technical install teams, as well as those ‘outside’ the Bluecoat such as external press, fabricators, and visitors.

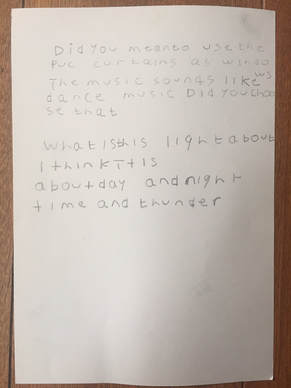

that goes there

|

SCENE 1: CURATOR TO CURATOR

In the Makin Room, Bluecoat. The group are interviewing Bluecoat’s in-house curator Adam Smythe about his exhibition Left Hand to Back of Head, Object Held Against Right Thigh. Tony asks a question about the artworks placement in the gallery. JADE: So Tony’s question; do you want to read it Tony or shall I? TONY: You. [ I gave Tony the option because I know he cannot read well and he particularly doesn’t appreciate being put on the spot to do so in front of people] JADE: So this is in the gallery that backs onto Radio Merseyside. Did you mean to use the curtains as windows and put them opposite windows? Is there a connection? So you have three curtains that look like three windows opposite three windows? He was wondering if that was on purpose? Is that something you think much about when you put work in spaces? ADAM: That’s a really really good observation. And yeah you always have to kind of think about this when you start to put an exhibition together in an empty gallery space, but of course it’s not completely empty, it’s not neutral there’s things that already exist in the gallery like those windows, they’re there and you have to deal with them in some way. And yeah, finding a place where the art feels right in that spot. The fact that the curtains kind of mirror what’s happening with the windows, you do think about. |

|

This scene was part of a much longer conversation with Adam in which the group interviewed him about an exhibition he had at the time recently curated at Bluecoat. This conversation took place during the first ’research’ phase of the project on the 21st of February 2016, to support the group to learn about different approaches to curating from a curator’s personal perspective. This scene focuses on questions Tony had in regards to where artworks were displayed in the gallery, and reasoning behind Adams choices to put them there. Tony always demonstrated a keen eye in noticing where items were located, but also looked for reasons why. He was keenly aware that artwork placement was deliberate. This conversation prompted us to assess the space we were using and look for, as Adam describes, “the things that already exist in the gallery”.

Imagining where work would go in the gallery was often difficult for the group. Even Eddie, whom has been visiting the Bluecoat on average three times per week for twenty years struggles to remember and describe the physical attributes of the gallery spaces. To support the group in deciding where works might go, I suggested making a model of the gallery space that we could refer to in the studio or as Diana put it, “something to jog my memory”. |

Model of the Vide made by the curators, 2016

Model of the Vide made by the curators, 2016

We began making our model by visiting the gallery and making sketches, notes and taking photographs of the space around us. I split the group in half – one group concentrated on documenting the ground floor level and the other on the first and second floors. With the information collected, back in the studio we constructed a model of The Vide using cardboard we have collected. We painted it to match the colours of the gallery and included where windows, lifts, doors and radiators were positioned. Whilst this model was not precisely to scale, it did provide a practical, hands-on way for us to assess the space and think about the possibilities of where artworks could go. In later workshops as the commissions began to be realised, the group also made models of the artworks to be placed inside the model. It is common practice for curators to use models and other planning tools when curating an exhibition. However, in my experience most curators tend to use 2D scaled floor plans, as appose to 3D models like the group.

In our final workshop before the exhibition opened, I was able to work with the group in the empty gallery space where their show would be installed. In this final workshop, we discussed where each item to be included in the show would be best placed to feedback to the artists, there were certainly differences in opinion. The group had different views on where some of the artworks would be best placed. For example, Diana and Hannah felt that James’ large-scale seed should be placed in front of the main ground floor window to benefit from the light. They also felt it would make an impact on visitors as this would be the first piece they would see upon entering the space. Other members of the group felt like it would be “stuck out on its own” and would “not look right”. Much of Tony and Leah’s views were instinctual and they gave little reason other than it did not “feel right”.

However, the artworks placement had been discussed between the artists and curators throughout the project, so there were no surprises when the group shared their final plans. Placement emerged from a very natural process of collaboration, and most decisions were also in light of practical considerations. For example, James’ sculpture was commissioned specifically to fit in The Vide’s ‘drop’, Mark required a large wall for his projection as well as access to electricity points and the film needed to be positioned in easy view for visitors. Here we see the relationality of curating, not just between people, but also between structures and objects. Whilst much of the decisions were joint, on occasion the artists were very clear on their wishes regarding particular aspects of their install. For instance, the curators had chosen where Alaena’s paintings would be situated within the gallery, however, Alaena was very clear on how she wished her paintings to be hung (such as the order) and provided plans for the curators and technicians. The curators were happy with this arrangement and in a Skype conversation with Alaena Eddie commented; “well you know them best don’t you” when she discussed sending over plans.

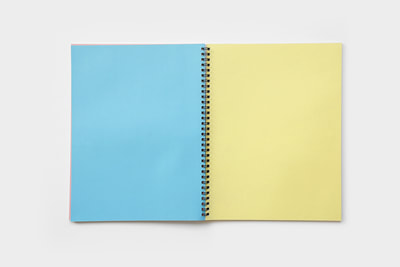

Whilst all curators invest time thinking carefully about the placement of artworks in the gallery, and specifically how these placements generate connections between artworks, the outcome of the exhibition installation can lead to “surprise moments” (Acord, 2010, p.455) wherein curators observe new emergent themes or relations between artworks not planned for or anticipated. This occurred during the third day of Auto Agents install. Alaena’s work has been installed on the opposite wall to Mark’s Book projection. As a technician thumbed through the pages, animating The Vide wall, he left Book open on its colour block middle section. These middle pages illuminated the gallery in pastel pink and blue, and directly opposite hung Alaena’s pastel colour block paintings. “That’s clever” pointed out another technician working on the ground floor, as he gestured between the two artworks opposite each other, and when the exhibition opened to the public, many thought that the middle section of Book was a deliberate nod to Alaena’s work. In fact, it was a surprise moment.

Whilst all curators invest time thinking carefully about the placement of artworks in the gallery, and specifically how these placements generate connections between artworks, the outcome of the exhibition installation can lead to “surprise moments” (Acord, 2010, p.455) wherein curators observe new emergent themes or relations between artworks not planned for or anticipated. This occurred during the third day of Auto Agents install. Alaena’s work has been installed on the opposite wall to Mark’s Book projection. As a technician thumbed through the pages, animating The Vide wall, he left Book open on its colour block middle section. These middle pages illuminated the gallery in pastel pink and blue, and directly opposite hung Alaena’s pastel colour block paintings. “That’s clever” pointed out another technician working on the ground floor, as he gestured between the two artworks opposite each other, and when the exhibition opened to the public, many thought that the middle section of Book was a deliberate nod to Alaena’s work. In fact, it was a surprise moment.

Throughout our research phase, we spent a lot of our time recording various forms of interpretation in a number of galleries. The primary issue the group came across time and time again was that of text and difficulties in reading. Most members of the group would bypass and ignore any gallery texts displayed. They never picked up hand outs, press releases or brochures and would occasionally ask me to read out labels to copy the artists name down in their sketchbook. We found that often approaches to interpretation were “chiefly literary” (Kuh, 2001, p.52), therefore the group learnt from the research phase was that traditional textual interpretation may not be appropriate for their exhibition.

The practice of interpretation addresses how we “facilitate encounters between object and observer” (Belcher, 2012, p.649). In particular, the crux of curatorial practice in contemporary art is the construction of artistic meaning through the exhibition, which is largely down to the curator. As Greenberg et al. (1996, p. 2) describes, “Part spectacle, part socio-historical event, part structuring device, exhibitions—especially exhibitions of contemporary art—establish and administer the cultural meanings of art”, and interpretation plays a key role in this. But from reviewing the literature, the very nature and role of interpretation in museums and galleries is complex and widely debated; from its role and scope, its relationship with learning, ethical entanglements, to its professionalisation and incorporation into job roles and departments.

In 1957, Freeman Tilden produced a seminal text on interpretation titled Interpreting Our Heritage, and within this text he famously sets out 6 principles of interpretation. Crucially, Tidlen points out that “the chief aim of interpretation is not instruction but provocation” (Tilden, 2007, p.18). Here, emphasis is placed on supporting people to make their own connections. Similarly, Cheryl Meszaros, a lecturer and museum consultant, claims constructivist learning theory[1] has undermined the traditional authority of art historical knowledge formerly used to empower art curators to dispense interpretation to the masses. Meszaros suggests power has now shifted to viewers, obliging curators to ask what (and how) museum visitors may be learning (2007). As a result, Meszaros argues, “people make their own meaning in and through their interactions with the world” (p.18). Arisen is the notion that the museum is all about you-the-visitor and your interpretations rather than learning being about the “consumption” of ideas (ibid).

From the beginning, the group were always interested in using film within their show as a way of ‘telling audiences about it’. I talked to Eddie in particular about why the Matisse film featured in Act 2: Scene 2: Fella With The Scissors, resonated with him so much. “The film makes you want to look at it and look at it some more. See how the paper is crinkly there” Eddie explained. “I really want to have a go at making that, can we?”. With Tilden’s principles in mind, was seeing the process of making a provocation for Eddie? Does this explain why he, and others in the group, were so keen for their own interpretative materials to show audiences the ‘making’ process?

In 1996 ex-director of Tate Museums and newly appointed chair of Arts Council England Nicholas Serota wrote; “The best museums of the future will… seek to promote different modes and levels of ‘interpretation’” (Serota, 1996, p.55). Serota suggested; “the story line becomes less significant and the personal experience becomes paramount… An increasing number of museums are following this model, prompting us to ask whether the museum is losing its fundamental didactic purpose” (p.10). This comment suggests that each of us, curators and visitors alike, will have to become more willing to chart our own path in the gallery experience, rather than following a single trajectory laid down by a curator or institution. Serota’s comments from twenty years ago hint at the relational turn of the museum and the emergence of audience-orientated art and relational aesthetics which would dominate in the early 2000s.

There is some literature that explores how learning disabled artists have approached the labelling and interpretation of their work. The chapter A Sense of Self by Dorothy Atkinson and Fiona Williams (1990) explores how many artists with disabilities featured in their publication identify themselves and their work through their “immediate environment” (p.11). Therefore many of the case studies demonstrate learning disabled artists using texts resembling ‘life stories’ in conjunction with their visual art, typically produced via interviews with support workers. However upon reflection, this approach was identified as problematic by both the authors and support workers; “When we listened afterwards to the tapes, we were struck by how easy it is to talk the person down tracks they might not necessarily have gone down… to ask about particular things that interested us” (p.228). Whilst there is literature exploring how learning disabled people have challenged labelling of their disabilities (label jars not people, learning difficulty not disability), there has been little work addressing how learning disabled artists have challenged traditional approaches to labelling and interpretation of themselves and their work in in museums and galleries contexts. This is an area I have identified where this study could contribute new thinking.

Developing the exhibition’s interpretation also raised issues surrounding the use of labels more broadly, for example; how and/or when is it acceptable to label artwork produced by or in conjunction with a person with a learning disability? Some believe that the artwork should always speak for itself and that a person’s “diagnostic label” (Fox and Macpherson, 2015, p. 12) should not be drawn attention to. Labels can work to differentiate groups, and in doing so they can stigmatize. But by excluding the biography of the artist and their learning disability, we perhaps miss the political work their art may achieve which was a very real debate that took place during the curation of Auto Agents outlined further on page 71. However, Outsider Artists for example have achieved considerable commercial success from practicing under labels connected to marginalisation, sharing with audiences their 'outsider' label. In the chapter To Label the Label? 'Learning disability' and exhibiting 'critical proximity' Helen Graham describes the complexities of labelling specifically in regards to learning disabled people within museum contexts. Through drawing upon the example of Mabel's Certificate (2004), an object belonging to a person with the label of learning disability that was displayed at The Museum of Croydon, Graham describes how labels are not simply “descriptive but productive” (2011, p.115), highlighting the thorny relationship between labelling objects and labelling people; recognising both the political utility in that labels make visible and articulate difference and inequality, and also their limitations such as over determining, and potentially, fixing difference.

The practice of interpretation addresses how we “facilitate encounters between object and observer” (Belcher, 2012, p.649). In particular, the crux of curatorial practice in contemporary art is the construction of artistic meaning through the exhibition, which is largely down to the curator. As Greenberg et al. (1996, p. 2) describes, “Part spectacle, part socio-historical event, part structuring device, exhibitions—especially exhibitions of contemporary art—establish and administer the cultural meanings of art”, and interpretation plays a key role in this. But from reviewing the literature, the very nature and role of interpretation in museums and galleries is complex and widely debated; from its role and scope, its relationship with learning, ethical entanglements, to its professionalisation and incorporation into job roles and departments.

In 1957, Freeman Tilden produced a seminal text on interpretation titled Interpreting Our Heritage, and within this text he famously sets out 6 principles of interpretation. Crucially, Tidlen points out that “the chief aim of interpretation is not instruction but provocation” (Tilden, 2007, p.18). Here, emphasis is placed on supporting people to make their own connections. Similarly, Cheryl Meszaros, a lecturer and museum consultant, claims constructivist learning theory[1] has undermined the traditional authority of art historical knowledge formerly used to empower art curators to dispense interpretation to the masses. Meszaros suggests power has now shifted to viewers, obliging curators to ask what (and how) museum visitors may be learning (2007). As a result, Meszaros argues, “people make their own meaning in and through their interactions with the world” (p.18). Arisen is the notion that the museum is all about you-the-visitor and your interpretations rather than learning being about the “consumption” of ideas (ibid).

From the beginning, the group were always interested in using film within their show as a way of ‘telling audiences about it’. I talked to Eddie in particular about why the Matisse film featured in Act 2: Scene 2: Fella With The Scissors, resonated with him so much. “The film makes you want to look at it and look at it some more. See how the paper is crinkly there” Eddie explained. “I really want to have a go at making that, can we?”. With Tilden’s principles in mind, was seeing the process of making a provocation for Eddie? Does this explain why he, and others in the group, were so keen for their own interpretative materials to show audiences the ‘making’ process?

In 1996 ex-director of Tate Museums and newly appointed chair of Arts Council England Nicholas Serota wrote; “The best museums of the future will… seek to promote different modes and levels of ‘interpretation’” (Serota, 1996, p.55). Serota suggested; “the story line becomes less significant and the personal experience becomes paramount… An increasing number of museums are following this model, prompting us to ask whether the museum is losing its fundamental didactic purpose” (p.10). This comment suggests that each of us, curators and visitors alike, will have to become more willing to chart our own path in the gallery experience, rather than following a single trajectory laid down by a curator or institution. Serota’s comments from twenty years ago hint at the relational turn of the museum and the emergence of audience-orientated art and relational aesthetics which would dominate in the early 2000s.

There is some literature that explores how learning disabled artists have approached the labelling and interpretation of their work. The chapter A Sense of Self by Dorothy Atkinson and Fiona Williams (1990) explores how many artists with disabilities featured in their publication identify themselves and their work through their “immediate environment” (p.11). Therefore many of the case studies demonstrate learning disabled artists using texts resembling ‘life stories’ in conjunction with their visual art, typically produced via interviews with support workers. However upon reflection, this approach was identified as problematic by both the authors and support workers; “When we listened afterwards to the tapes, we were struck by how easy it is to talk the person down tracks they might not necessarily have gone down… to ask about particular things that interested us” (p.228). Whilst there is literature exploring how learning disabled people have challenged labelling of their disabilities (label jars not people, learning difficulty not disability), there has been little work addressing how learning disabled artists have challenged traditional approaches to labelling and interpretation of themselves and their work in in museums and galleries contexts. This is an area I have identified where this study could contribute new thinking.

Developing the exhibition’s interpretation also raised issues surrounding the use of labels more broadly, for example; how and/or when is it acceptable to label artwork produced by or in conjunction with a person with a learning disability? Some believe that the artwork should always speak for itself and that a person’s “diagnostic label” (Fox and Macpherson, 2015, p. 12) should not be drawn attention to. Labels can work to differentiate groups, and in doing so they can stigmatize. But by excluding the biography of the artist and their learning disability, we perhaps miss the political work their art may achieve which was a very real debate that took place during the curation of Auto Agents outlined further on page 71. However, Outsider Artists for example have achieved considerable commercial success from practicing under labels connected to marginalisation, sharing with audiences their 'outsider' label. In the chapter To Label the Label? 'Learning disability' and exhibiting 'critical proximity' Helen Graham describes the complexities of labelling specifically in regards to learning disabled people within museum contexts. Through drawing upon the example of Mabel's Certificate (2004), an object belonging to a person with the label of learning disability that was displayed at The Museum of Croydon, Graham describes how labels are not simply “descriptive but productive” (2011, p.115), highlighting the thorny relationship between labelling objects and labelling people; recognising both the political utility in that labels make visible and articulate difference and inequality, and also their limitations such as over determining, and potentially, fixing difference.

|

Uniquely, Auto Agents is predominantly a text free exhibition, reflecting the ways in which the curators differently read, write and communicate. Therefore, the curators of Auto Agents thought long and hard about the inclusion of text into their own exhibition, and decided it was an opportunity to ‘do it their own way’ and relate the approaches to curating to their ‘big idea’ of autonomy. Rather than traditional labels, text panels and wordy artist statements and hand-outs, Auto Agents instead featured a single short video filmed collaboratively between themselves and the artists (left).

|

The video which is just under three minutes long begins with the curators introducing themselves the starting point for the exhibition; their own lives and experiences. “We the curators all have something in common” Leah’s voice-over explains on the video, “We have different kinds of independence and different levels of support. We wanted the artists to think about these things, and what’s interesting is, everyone made something which involves action” (French, 2016). Although the concept of autonomy is highly politicised for learning disabled people as previously discussed, through their work with the curators the artists in Auto Agents interpreted that concept and made it their own. In addition, the video includes short segments made by each artist filmed throughout the curatorial process, providing a window into the relational and participatory approaches to creating the exhibition. The curators in the video do not explain or give reason to what the work is about like some types of interpretation, that is left to the artists.

Just as text was not employed as a mode of communication inside the exhibition, the curators also chose not to use text as the primary way to market their exhibition either. Instead, the group collaborated with Mark to produce a series of gifs (above). An animated GIF (Graphics Interchange Format) file is a graphic image on a web page that moves, presenting short sequences which loop endlessly. Gifs had been of interest to the group since James’ initial workshop in which he shared his Charlie and the Chocolate Factory gif. Mark also became interested in gifs as felt mutual themes of action and movement were present in his work with the group. After a workshop in which we all made our own practice gifs for a Bluecoat exhibition, Mark designed three gifs for Auto Agents with direction from the curators.

Just as text was not employed as a mode of communication inside the exhibition, the curators also chose not to use text as the primary way to market their exhibition either. Instead, the group collaborated with Mark to produce a series of gifs (above). An animated GIF (Graphics Interchange Format) file is a graphic image on a web page that moves, presenting short sequences which loop endlessly. Gifs had been of interest to the group since James’ initial workshop in which he shared his Charlie and the Chocolate Factory gif. Mark also became interested in gifs as felt mutual themes of action and movement were present in his work with the group. After a workshop in which we all made our own practice gifs for a Bluecoat exhibition, Mark designed three gifs for Auto Agents with direction from the curators.

Interpretation film inside gallery

Interpretation film inside gallery

This methodology in developing interpretation for Auto Agents illuminates the participatory and relational potential of curating. For me, it also exemplifies the potential for the process of curating to be politicised. The non-existence of text in Auto Agents challenges the norms of the gallery domain, which often rely on text, and contributes towards activating change within the institution itself through providing new solutions to areas of previous tension. The group chose to use their capacity as curators to orientate audiences to their ways of understanding art, which emphatically for them, is not through text. This disruption of the status quo could also be viewed in light of philosopher Jacque Rancière’s writings on politics which he describes is not what is often thought of as politics, such as the exercise of power from bureaucracies which he renames 'la police', politics is really what occurs when the dominant social order is disrupted (Rancière, 2001). In this context, the exclusion of text disrupts the ‘dominant order’ within the institution opening up new possibilities of ways to ‘know’ about art. But this was not easy. As curator Diana succinctly explained; “People might think we aren’t using text because we can’t do it, instead of saying, here’s a new way and it’s good”. By excluding text the curators drew attention to their status as learning disabled people, but at the same time, they foregrounded an important quality for activism; the ability to view and imagine the world differently through forging new relations. This approach to interpretation also enabled visitors to experience a more relational engagement with the art work as meaning was not mediated via text which is inaccessible to many people. However, despite great efforts on the part of design teams and curators, “it is well documented that many visitors do not view exhibits in the intended order” (Falk and Dierking, 2011, p.71). We gained some feedback that people did not understand what the exhibition was about. When asked if they had watched the video, they said no, presenting a limitation with using video as interpretation.

the show must go on

The installation of Auto Agents was a bumpy ride. Although the curators had engaged in lengthy, detailed discussions and workshops with the artists over a long period of time, the reality is that they, (and curators everywhere engaging in commissioning) could not know the final outcome of the commissioned work in advance nor prepare for what they would experience in their first encounter with the finished work.

As we experienced, the installation process can have considerable impact on the final exhibition. As Sophia Krzys Acord succinctly describes in her paper The Practical Work of Curating Contemporary Art (2010), installing art exhibitions throws up a myriad of unexpected practical and authorial decisions. Artists may change their minds and “edit works in progress” or make “visual decisions” about placement once inside the actual space (p.453). This means installing art exhibitions can take a considerable amount of time, with Auto Agents taking an average week to install. The bulk of this time Acord suggests is spent moving things around, stepping back, looking at them, adjusting them, and perhaps moving them again based on a curator’s sense of what ‘feels right’. Therefore, exhibition installations can be seen as a combination of plans and “situated actions” (ibid). As Lucy Suchman (1987) notes in her study of human-machine interaction, while action is generally described as adhering to coherent plans, in practice these plans are necessarily vague and action is actually accomplished via ad hoc ‘situated actions’. Curators make no pretence to fool-proof plans for exhibitions but often respond to the spontaneous nature of situated actions that occur through installation.

As we experienced, the installation process can have considerable impact on the final exhibition. As Sophia Krzys Acord succinctly describes in her paper The Practical Work of Curating Contemporary Art (2010), installing art exhibitions throws up a myriad of unexpected practical and authorial decisions. Artists may change their minds and “edit works in progress” or make “visual decisions” about placement once inside the actual space (p.453). This means installing art exhibitions can take a considerable amount of time, with Auto Agents taking an average week to install. The bulk of this time Acord suggests is spent moving things around, stepping back, looking at them, adjusting them, and perhaps moving them again based on a curator’s sense of what ‘feels right’. Therefore, exhibition installations can be seen as a combination of plans and “situated actions” (ibid). As Lucy Suchman (1987) notes in her study of human-machine interaction, while action is generally described as adhering to coherent plans, in practice these plans are necessarily vague and action is actually accomplished via ad hoc ‘situated actions’. Curators make no pretence to fool-proof plans for exhibitions but often respond to the spontaneous nature of situated actions that occur through installation.

As outlined in the section That Goes There, the curators spent the first day of the install finalising where things would go. However, they did not have the benefit of the artwork in situ and so their decisions were instead supported by plans and models. The main difficulty of Auto Agents’ installation began when James’ fabricator let him down and could no longer produce an integral metal part of his moving sculpture. This happened on the second day of the install when James had already delivered the majority of his work to Bluecoat. Without this piece, James was required to reconfigure his sculpture on site. Instead of moving parts inside the main sculpture as originally planned, the moving parts now operated outside the main sculpture as a separate piece of work. For the technicians, this change ensured that the piece was safe for audiences to operate, and for myself and James, it still in some way spoke to the curators’ vision of movement controlled by audiences as per the original design. This recalibration of the artwork required rapid-fire problem solving. As well as addressing practicalities of changing the sculpture such as re-wiring, PAT testing and the ingenious fabrication of a wooden gear complete with marble ball bearings. But there was also the less obvious and implicit process of changing the work in terms of ‘signing off’ on the authorial content. In other words, did these changes in the artwork still fulfil the curators original brief for the commission? After all, we were not only accountable to the curators’ vision for the commission, but also to the Arts Council England from whom the funds for the commission was awarded. For me, in this aspect of the project, the networks of people underpinning the gallery emerged. Not only though Bluecoat’s own staff – Adam, Marie-Anne, Bec and the numerous technicians - but also institutionally affiliated individuals and groups like engineers and electricians. Explaining these networks to the group was supported using Hannah’s ‘independence’ artwork outlined in Act 2: So, What is a Curator Anyway? Just as Hannah requires networks of people and support to enable her to attend performance group, wonderfully detailed in her art, commissions and artworks also require networks of people and support to be made and exhibited.

The curators however, were left out of these situated actions. Whilst this was not the only change to occur with commissions[2], it was the first change to occur without the curator’s consent. Due to their tightly managed schedules, they could only be around for the pre-agreed one-day per week and I was entrusted to manage the process on their behalf. Here we see how learning disabled people’s live are incredibly risk averse; it was impossible to change people’s schedules and ‘risk’ them ‘losing out’ on their usual routines and projects. If I could undertake this study again, I would insist the curators would be present during the entirety of the installation to ensure their inclusion if any decisions on situated actions that may arise.

The curators first encounter with Auto Agents brimmed with excitement, but then confusion sank in. Bluecoat’s lobby was already filling up to what would be an incredibly busy private view (images below). Away from the crowds, the group, one by one as they arrived came to look around the show. They only had a couple of minutes before the speeches started and audience would be let in. This did not give me near enough the amount of time required to explain the series of changes that had occurred over just a few days. Upon reflection, it is interesting to think that an object such as James’ metal mechanism not being fabricated threw off months of preparation and planning. This demonstrated how in the final stages of an exhibition the work becomes materially bound. Objects, such as James’ mechanism, have non-objective consequences for mediation; they do not simply perform the ‘scripts’ they are given and objects, just as much as people, can produce significant effects[3].

The curators first encounter with Auto Agents brimmed with excitement, but then confusion sank in. Bluecoat’s lobby was already filling up to what would be an incredibly busy private view (images below). Away from the crowds, the group, one by one as they arrived came to look around the show. They only had a couple of minutes before the speeches started and audience would be let in. This did not give me near enough the amount of time required to explain the series of changes that had occurred over just a few days. Upon reflection, it is interesting to think that an object such as James’ metal mechanism not being fabricated threw off months of preparation and planning. This demonstrated how in the final stages of an exhibition the work becomes materially bound. Objects, such as James’ mechanism, have non-objective consequences for mediation; they do not simply perform the ‘scripts’ they are given and objects, just as much as people, can produce significant effects[3].

In the workshop following the private view, we scheduled a proper look around the exhibition away from the crowds and evaluated it as a group. I ran this evaluation workshop by using Edward De Bono’s six thinking hats, a tool for group discussion and thinking involving six coloured hats which each represent a different mode of thinking; (Blue Hat – The control or management, White Hat – Information, Red Hat – Emotions, Black Hat – Discernment, Yellow Hat – Optimistic response, Green Hat – Creativity).

|

SCENE 2: BLACK HAT

The group are using DeBono’s six thinking hats to evaluate the exhibition. Jade: Now we’re going to move onto Hannah’s hat Diana: Hannah’s is the black hat! Jade: So Hannah’s black hat is the problems, what didn’t go right? [The group go quiet] Jade: No? No problems?! So, everything has been completely perfect? Donna: Was the art what you expected? Eddie: I say it wasn’t, we wanted to see things move around the pole. Jade: Great, thank you Eddie. So, a black hat problem was the artwork didn’t move as planned? Eddie: It’s bad on his part I think. He should’ve had it all ready. |

Eddie was cross. He was angry at the private view, and he was still annoyed in the following workshop. During this time, I concentrated on listening to the group’s feelings on the exhibition and on explaining the culmination of circumstances that brought about the changes to the work in the first place. I also felt that the group would likely have felt differently if they had experienced the extreme pressure of the situation. In some ways, they were protected from this. Whilst having the curators on site during the install is clearly the best way to mitigate this sort of situation in the future, if curators could not be on site then a solution could be to record the chain of events. Perhaps recording the circumstances via video for example, interviews with technicians, then the issues at stake could have been more tangible for the group.

Interestingly, I sensed Eddie, Tony and Diana – the three Blue Room members – found it hardest to accept the difficulties in the install. However, Hannah in particular demonstrated great understanding about the risk involved. In the workshop, Eddie postulated that maybe, the exhibition should not have opened that day if it was not ready. But Hannah responded by saying “but the show must go on”. Donna explained this is something they discuss in her performing arts group Ella Together and that ‘things seen as going wrong’ are often a very real part of shaping art.

Interestingly, I sensed Eddie, Tony and Diana – the three Blue Room members – found it hardest to accept the difficulties in the install. However, Hannah in particular demonstrated great understanding about the risk involved. In the workshop, Eddie postulated that maybe, the exhibition should not have opened that day if it was not ready. But Hannah responded by saying “but the show must go on”. Donna explained this is something they discuss in her performing arts group Ella Together and that ‘things seen as going wrong’ are often a very real part of shaping art.

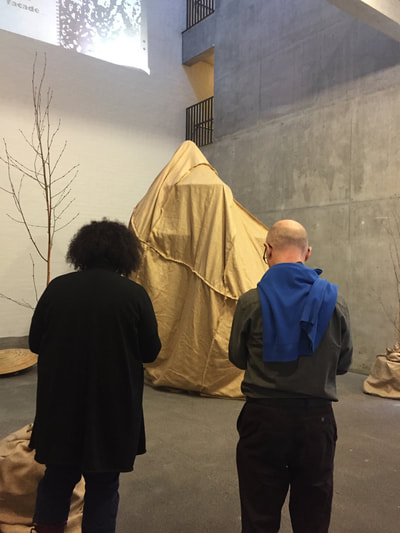

james harper: meet at the tree

James completed commission was an installation titled Meet at the Tree. It comprised of a large central sculpture which was based on the concept of a tree, covered in a large draped blanket of hessian. Behind this sculpture was a mechanical seed shape, which audiences could control via a switch on the wall. When on, the seed would continually rotate which for James was an important link to the curator’s concept of autonomy. Either side of the large sculpture, James included two real live birch trees as well as large hand sculpted wooden seed varnished in linseed oil positioned on the floor. Along two walls of The Vide, and on the wall of the upstairs level of the gallery, James also installed small sculptures which resembled stones. These clay sculptures were directly informed by workshops with the group. The concept broadly underpinning James’ installation is community. In the interpretation video James explains;

|

The tree is a symbol of so many different things from landmarks, to sources of food and shelter. When I was growing up, friendship groups always had a landmark which was a meeting point, for me this was the tree. There’s a Costa Rican saying that if you have a church, a bar and a football, you have a town but I feel a tree is far more important in terms of community.

|

mark simmmonds: book

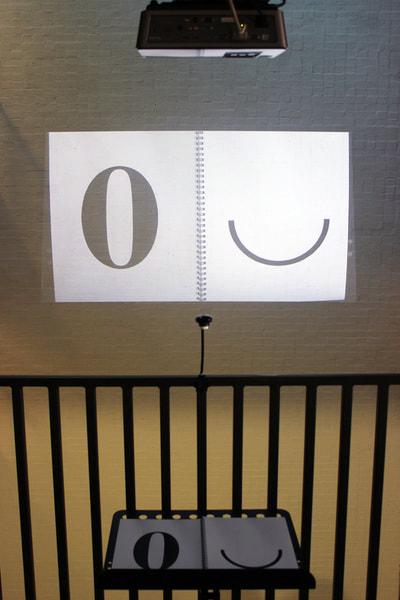

Book, 2016

Book, 2016

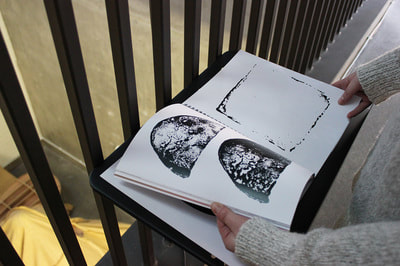

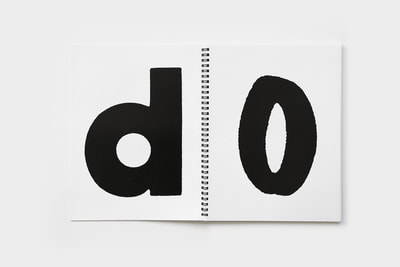

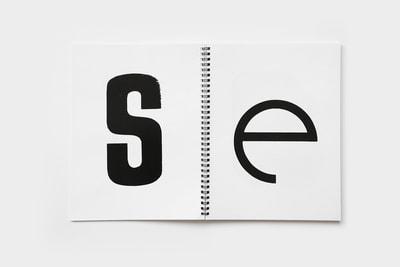

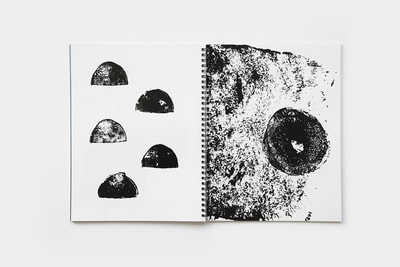

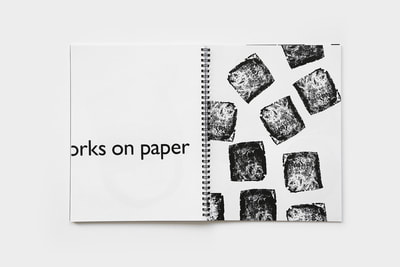

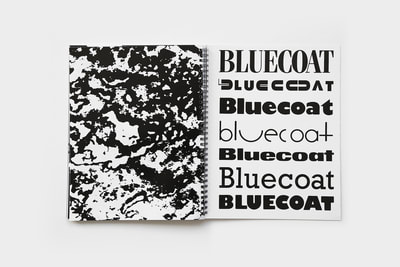

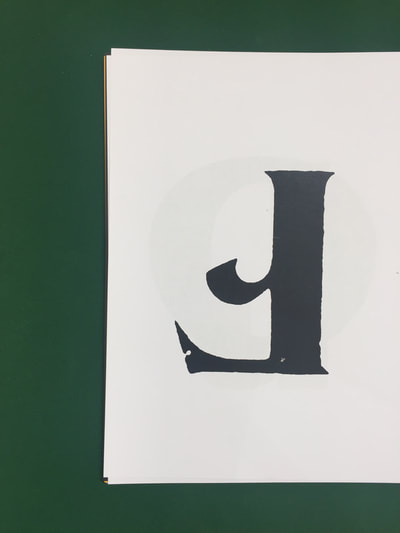

Mark’s completed commission is titled Book. It aims to reimagine the purpose of gallery publications through the eyes of the curators who employ alternate ways of ‘reading’. It is an A4, spiral bound publication broadly comprising of three sections. The first section of Book sets out the question ‘What do you use books for?’ through placing each letter of this question on a separate page. Each of these individual letters were scanned from ephemera found inside Bluecoat’s own library, used as a source for the group in their workshops. By drawing out the question across many pages, Mark complicates and disrupts the reading experience for audiences, inspired by working with the group. He was also drawing attention to the uniqueness and design of typefaces by enlarging each letter on a single page.

Section two contains no text, but colourful textured pages. This has been described as an ‘explosion’ within the book, a surprise for the reader following the previous black and white section, like Dorothy entering the Technicolor land of Oz. The third and final section is a mixture of Bluecoat ephemera such as old logos and slogans the group found in their library workshops, as well as prints made by the group. Here the publication draws into dialogue old events and exhibitions throughout Bluecoat with the groups own contemporary artworks.

Book highlights the experiential and sculptural elements of books; the action of page turning, colour, form, paper weight and texture. The experiential dimension of ‘reading’ is also explored via Books display in the gallery. Instead of displaying it on a plinth or table, which for the group produced a “boring” and static experience, they challenged Mark to devise a participatory way to include it in the gallery. Inspired by a book lecture he saw online, Mark proposed using a live camera positioned over Book to project its image into the space. Mark demonstrated this idea to the group during a workshop using an iPad connected to a projector. Hannah in particular engaged with this idea and pushed for its inclusion in the final exhibition.

Section two contains no text, but colourful textured pages. This has been described as an ‘explosion’ within the book, a surprise for the reader following the previous black and white section, like Dorothy entering the Technicolor land of Oz. The third and final section is a mixture of Bluecoat ephemera such as old logos and slogans the group found in their library workshops, as well as prints made by the group. Here the publication draws into dialogue old events and exhibitions throughout Bluecoat with the groups own contemporary artworks.

Book highlights the experiential and sculptural elements of books; the action of page turning, colour, form, paper weight and texture. The experiential dimension of ‘reading’ is also explored via Books display in the gallery. Instead of displaying it on a plinth or table, which for the group produced a “boring” and static experience, they challenged Mark to devise a participatory way to include it in the gallery. Inspired by a book lecture he saw online, Mark proposed using a live camera positioned over Book to project its image into the space. Mark demonstrated this idea to the group during a workshop using an iPad connected to a projector. Hannah in particular engaged with this idea and pushed for its inclusion in the final exhibition.

|

|

|

For the exhibition, Book was situated on the second level of the gallery space. When entering the gallery on the ground floor, visitors were unaware that the projected image of the book pages positioned high on The Vide wall was actually a live camera. Then when a visitor travelled to the second floor and looked through the publication, their experience would appear via a large projection onto The Vide wall. For me, it was interesting to see the many ways the live camera was used or (perhaps misused!) by visitors. On one occasion, I saw a large group of teenage boys playing an elaborate game of Pokémon Go using the camera. I also saw several notes left under the camera, as well as flyers for gigs and stores, transforming the gallery into a giant advert.

In addition to producing Book, Mark also worked with the group to create vinyl designs throughout the gallery. This included the exhibition title on the ground floor window, footprints in front of the film screen and his installation (signally to visitors to stop), as well as arrows on the floor and walls which acted both as practical signage indicating that the show was across two floors, but also fed into Leah’s description of the exhibition featured in the film that the exhibition was about movement and action.

alaena turner: secret action paintings

Secret Action Paintings, 2016

Secret Action Paintings, 2016

Alaena exhibited three paintings in Auto Agents from her series titled Secret Action Paintings. Alaena has been making this series since 2008 and during this time has developed a technique for making a painting directly on the wall of an exhibition space, using oil-paint as glue to attach pieces of coloured wood to the wall. Alaena calls these works Secret Action Paintings because they are always shown in a state of stillness, as a static installation or image, so the ‘action’ of the works falling off the wall is not seen by the gallery audience as a ‘live event’, instead it is implied by the marks on the wall and panels on the floor. Alaena describes; “I intend for these to be read as propositions for how you might make a painting, accepting and exhibiting moments of accident and mess.” The title of the series is also a reference to the early abstract paintings of ‘action painters’, such as Jackson Pollock, and the theatrical nature of the ‘drip’ in painting. Alaena plans to continue making paintings directly in exhibition spaces using this technique, which is intended to show an unexpected quality of painting materials (its potential as an adhesive), and to allow the materials of painting to perform for an audience. She also intends to continue recycling the pieces of wood to make collage paintings, incorporating the dents the wood gathers from falling to the floor, and the stains from the oil-paint as part of the image of the painting.

Alaena began making the paintings in her studio by cutting multiple pieces of wood and then using acrylic paint to achieve a flat monochrome surface of the wood. The painting is completed onsite in the exhibition space by painting the back of these pieces of wood with oil-paint and then physically attaching the pieces of wood to the gallery wall or to each other, using oil-paint as glue. This process of attaching the pieces of coloured wood to the wall using oil-paint as glue is a way to explore chance mark-making and accident. Often the weight of the wooden panel will cause it to fall off the wall, creating a mark on the gallery wall or floor, documenting the act of making a painting.

Alaena began making the paintings in her studio by cutting multiple pieces of wood and then using acrylic paint to achieve a flat monochrome surface of the wood. The painting is completed onsite in the exhibition space by painting the back of these pieces of wood with oil-paint and then physically attaching the pieces of wood to the gallery wall or to each other, using oil-paint as glue. This process of attaching the pieces of coloured wood to the wall using oil-paint as glue is a way to explore chance mark-making and accident. Often the weight of the wooden panel will cause it to fall off the wall, creating a mark on the gallery wall or floor, documenting the act of making a painting.

engagement events

In addition to the Auto Agents exhibition, several events ran alongside it. These events were broad in scope ranging from curator-led tours of the show, artist events, to events designed for specific audiences like students.

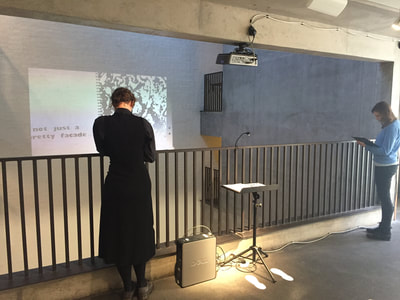

With the curators approval, Mark organised an event at Bluecoat titled What Do You Use Books For? This event was held in Bluecoat’s Library Room - the space he worked with the group in - on Thursday 12th January 2017. Mark presented a performance lecture based on the thinking behind Book as it in part explores different ways of reading, and the possibilities and constraints of the printed page as an active site for interaction and exchange. Mark included this quotation on the events invitation;

With the curators approval, Mark organised an event at Bluecoat titled What Do You Use Books For? This event was held in Bluecoat’s Library Room - the space he worked with the group in - on Thursday 12th January 2017. Mark presented a performance lecture based on the thinking behind Book as it in part explores different ways of reading, and the possibilities and constraints of the printed page as an active site for interaction and exchange. Mark included this quotation on the events invitation;

|

There was an old, delicate, lingering odour about it, such an odour as sometimes haunts an ancient piece of furniture for a century or more. The end-papers, inside the binding, were oddly decorated with coloured patterns and faded gold. It looked small, but the paper was fine, and there were many leaves, closely covered with minute, painfully formed characters (Machen, 1904, no pagnation)

|

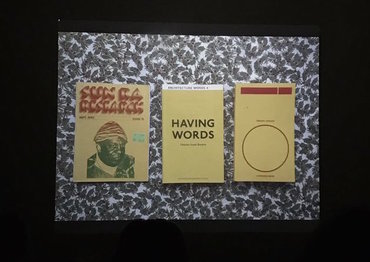

'Most Yellow Book'. Courtesy of Mark Simmonds, 2017

'Most Yellow Book'. Courtesy of Mark Simmonds, 2017

During the event Mark presented a slideshow of images. Each of the images illuminated publications, books and ephemera that Mark has experienced interesting encounters with in his life, and Mark talked audiences through these exchanges. One slide showed a book Mark picked up on holiday, another showed audiences his search for his ‘most yellow book’ and another depicted interesting coincident between authors. The event aimed to reveal the personal and relational components that books and publication support, inspired in part by many of the curators collecting books, despite them not reading in the traditional sense. The event was sold out and culminated with a walk through of Auto Agents.

To further engage audiences with the exhibition, the curators wanted to do visitor tours of the exhibition. During workshops, we practiced giving tours of the show but most of the group found it too difficult to remember and recall information about each artist and each piece. Tony and Hannah also did not enjoy public speaking in this way which meant much of the talking was left to the others. We also tried using prompts, such as photographs, but these worked to varying degrees of success for different members. Finally, we thought about how we as a group explored exhibitions and decided to try a completely different approach inspired by one of Blue Room’s methods of engaging with art. When Blue Room members explore a new exhibition, they sketch it. This is the approach we adopted in the first phase of our own research. This method not only produces a visual record of a visit, but the act of drawing supports people to really observe.

To further engage audiences with the exhibition, the curators wanted to do visitor tours of the exhibition. During workshops, we practiced giving tours of the show but most of the group found it too difficult to remember and recall information about each artist and each piece. Tony and Hannah also did not enjoy public speaking in this way which meant much of the talking was left to the others. We also tried using prompts, such as photographs, but these worked to varying degrees of success for different members. Finally, we thought about how we as a group explored exhibitions and decided to try a completely different approach inspired by one of Blue Room’s methods of engaging with art. When Blue Room members explore a new exhibition, they sketch it. This is the approach we adopted in the first phase of our own research. This method not only produces a visual record of a visit, but the act of drawing supports people to really observe.

Therefore, instead of leading visitors on a traditional exhibition tour, with the expectation of the curators verbally explaining their exhibition and works in it, we used this drawing approach and on tours of the exhibition we invited visitors to sketch the artwork with us as a way of looking and engaging. As we sketched together conversations and questions naturally came about. The curators would approach visitors as they drew which meant often they had multiple one-on-one discussions rather than a single conversation addressing the entire group. This meant that the shyer members could all participate. When the curators were ‘stuck’ and were unsure of what to say, they asked about what visitors were drawing and what they saw in the work instigating an active dialogue. Interpretation researchers Doug Knapp and Brian Forist advocate an active dialogue between the interpreter and visitors.

|

In a dialogic approach, the interpreter is aware of the visitors and the place in which they have gathered. The visitors are no longer seen as vessels to be filled with information or individuals not yet connected to resources. The respectful relationship between interpreter and visitors is at the center of the ensuing dialogue. (2014, p.35)

|

Dialogue-based interpretation is much less presentational than the traditional offerings. It is more about the visitors and their interaction with the objects than it is about the planned presentation of the interpreter. It attempts to veer programs from didactic one-way presentations to active two-way communication between the visitors and the interpretive message. This approach is more complex and challenging, but increases the potential for the visitors to make personal connections and therefore have lasting memories of their interpretive experience (ibid). However, not knowing a “specific trajectory” for a tour can be seen by some “as a process that lacks guidance and control” (p.37). But the concept of any process being structureless is contested, namely by Jo Freeman her influential essay The Tyranny of Structurelessness (2017). In this essay Freeman reflects on the experiments of the feminist movement in resisting the idea of leaders and even discarding any structure or division of labour. She suggests that for everyone to have the opportunity to be involved in any given group and to participate in its activities the structure “must be explicit, not implicit” (ibid). The rules of decision-making must be “open and available to everyone, and this can happen only if they are formalized” (ibid). In terms of the drawing tours, the ‘rules’ were clear; the audience would initiate and lead the conversation supported by observational drawing – the curator’s role was simply to respond. I found that this open-ended, emergent approach supported the curators to engage with visitors in-the-moment on their own terms, and importantly, with little intervention from me.

One of the final engagement events took place on Friday 13th of July, 15 members of PaRNet – the practice as research network – hosted one of their colloquiums at Bluecoat based on Auto Agents. PaRNet is made up of postgraduate research students undertaking creative practice-led research. They are based across the Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York but their meetings often include students from outside of these universities.

|

SCENE 3: THE ELEPHANT MAN

Jade and Eddie are leading a drawing tour, an approach devised by the curators, for students. Eddie: My name is Eddie and I helped put this show together… We’re going to look around it and draw it and talk about it. Jade: Rather than give a traditional tour where we explain the work to you, we would love to hear what you think the work means. Eddie: Yes, exactly that. [The group is handed drawing materials and begin to explore the space] Eddie: That’s a good picture. Student: Oh thank you, it’s quite hard to draw. But It reminds me of the elephant man, y’know with his hessian mask? Eddie: Does it now? Who’s that? Jade: Well, he was this man in Victorian times who had a condition which made him look very unusual. He had like, growths all over his body which people said made him look like an elephant. He used to wear a mask to cover himself and it was made out of a similar material to that Eddie: Well that is very interesting, do you think James knows that? Jade: I’m not sure, we’ll have to ask him. Eddie: …I think it’s a lot about hiding things away this one… but I never heard of that fella before. |

In this scene we see Eddie and a student discussing what the hessian material in James’ sculpture could mean. James’ large draped hessian sculpture was intended to reference the artist’s personal experiences of community, but on this drawing tour students convened around the piece and discussed concepts of restriction, of concealment and even drew parallels with Joseph Merrick’s (the ‘Elephant Man’) burlap sack used to conceal his condition. Eddie, and the other curators had never come across Joseph Merrick before and were very curious with this reference. For them it brought a completely new and historic resonance to James’ piece and they began sharing this in subsequent conversations around the work - despite it not being a deliberate reference intended by the artist. But on a different drawing tour, local councillors and disability health professionals also saw the draped hessian as a type of concealment, not of the individual as the students did, but of the dampening of ideas and practices. Feelings of restriction resonated in a different sense and from a different perspective, drawing the art work into new meaning.

Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett wrote in 1998 that “Museums were once defined by their relationship to objects: curators were ‘keepers’ and their greatest asset was their collections. Today, they are defined more than ever by their relationship to visitors” (p. 138). Curatorship has gradually evolved from an object-based practice towards a practice of exhibition-making based on community-driven projects and approaches. In her book, The Participatory Museum (2010), Nina Simon advocated that museums ought to become places geared towards social change - that is, places intended to change the world rather than only interpreting it. She and others (Sandell, 2010; 2012) suggest museums can be places that facilitate people’s understanding of their role and place in society, and hopefully find tools to better interact, communicate and share knowledge in order to bring about change. I believe drawing tours were a place that supported the curators and visitors to interact and share views and experiences with each other. More so than the more formal events, or even the launch, this is wear conversations took place.

|

Finally, it was great to see that Blue Room ran a workshop in response to Auto Agents. In this workshop, the curators gave a tour of the exhibition and the group proceeded to make artwork in response. The participatory nature of work appealed to the Blue Room cohort, but some struggled to draw out the theme of independence from the art work for themselves. Becky designed the workshop activities in response to the art works. Inspired by James’ spinning seed sculpture, Blue Room members explored words and made their own spinning sculptures reminiscent of those made in James’ very first workshop with the curators.

|

auto agents at the brindley

After Auto Agents closed at Bluecoat on the 16th January 2017, it went on to open again at the Brindley in Runcorn, Halton, from the 4th March to 15th April 2017. This move was never intended when the project was first designed, but came about through forging new links between Bluecoat and the Brindley brought about as the project developed. The exhibition at the Brindley, although it was the same work, was different. This came about in response to firstly, the different physical space of the gallery. The majority of the work in Auto Agents was commissioned specifically in mind for display in The Vide at Bluecoat. This is an unusual space with a cavernous drop. The Brindley’s space however is almost the opposite. The gallery is located in a round building, has curved walls creating a long thin space. Therefore the curators and artists had to think carefully about how to reconfigure the work into the space. This was made somewhat easier by the physical limitations of the space. The projector was already rigged up on one end of the gallery and the opposite end had temporary partitions which the curators felt could be used to create more of a ‘cinema’ feel.

Interpretation film in The Brindley, 2016

Interpretation film in The Brindley, 2016

They felt that the video when displayed in Bluecoat was often hard to watch as there were no seats, so at the Brindley they utilised the partition wall and included seats in this portion of the gallery. Secondly, the different institutional set up affected the show. The Brindley is a council run arts building as appose to Bluecoat which is a charity. We found that there was less institutional support with the exhibition due to the arts manager of the council recently leaving post and not being replaced. This meant we only ran one event during Auto Agents at the Brindley, which was designed by curator Leah.

Celebrate Me was the event organised by Leah as part of her business Positive You and supported on the day by myself. Throughout the project Leah had been looking for opportunities to bring her own work into the gallery and the Brindley presented a great opportunity for her as the dates coincided with World Down Syndrome Day on the 21st of March. Celebrate Me was a free drop in activity where visitors were invited to create their own celebratory bunting as part of a unique arts display. This event is all about celebrating the lives and dreams of people who have Down Syndrome, through creating a piece of bunting. Bunting is a decoration often used at parties which symbolises celebrations. Leah wanted to use this idea to help people celebrate their own lives and achievements and raise awareness of the potential people with Down Syndrome have when given opportunities and independence to make their own decisions. The event had a great turnout and many families with children with Downs Syndrome attended. The event made it into local newspapers, and subsequently myself and Leah were invited to be filmed inside Auto Agents for local TV news [4] to discuss events and the exhibition. This was perhaps one of the most successful events run as part of Auto Agents and if I was to run this study again, I would be more explicit in supporting each individual curator to generate their own engagement events.

Celebrate Me was the event organised by Leah as part of her business Positive You and supported on the day by myself. Throughout the project Leah had been looking for opportunities to bring her own work into the gallery and the Brindley presented a great opportunity for her as the dates coincided with World Down Syndrome Day on the 21st of March. Celebrate Me was a free drop in activity where visitors were invited to create their own celebratory bunting as part of a unique arts display. This event is all about celebrating the lives and dreams of people who have Down Syndrome, through creating a piece of bunting. Bunting is a decoration often used at parties which symbolises celebrations. Leah wanted to use this idea to help people celebrate their own lives and achievements and raise awareness of the potential people with Down Syndrome have when given opportunities and independence to make their own decisions. The event had a great turnout and many families with children with Downs Syndrome attended. The event made it into local newspapers, and subsequently myself and Leah were invited to be filmed inside Auto Agents for local TV news [4] to discuss events and the exhibition. This was perhaps one of the most successful events run as part of Auto Agents and if I was to run this study again, I would be more explicit in supporting each individual curator to generate their own engagement events.

[1] A theory in which people construct their own understanding and knowledge of the world, through experiences and reflecting on those experiences.

[2] In James’ original proposal he had hoped to suspend the main sculpture from the ceiling. However after seeking advice from a structural engineer, he decided against it and this was agreed with the curators.

[3] Actor Network Theory (ANT) was developed in the 1980s by Bruno Latour, Michel Callon and John Law. In short, ANT can be defined as a research method with a focus on the connections and relations between both human and non-human entities (Callon 1986; Latour 2005).

[4] Skip footage to 6 mins in to view the interview.