A c t 3 T h e C o m m i s s i o n e r s a n d T h e C o m m i s s i o n e d

During the second phase of the project, focus shifted from devising an exhibition theme to working with artists with an aim to find work for the show. Contemporary art curators have extensive networks and relationships with artists cultivated from years of experience in the sector, and this “ability to build relationships” is cited as a core competency of the curator’s role (National Career Service, 2016). Although it would be impossible to try and replicate this in a matter of months, what I did want to do is support the group to meet as many artists as possible in a bid for them to experience a variety of artistic forms, processes and approaches. To do this I contacted a well-known local artist-led studio in Liverpool called The Royal Standard and advertised for artists to deliver a two hour paid workshop with the group. I explained that the group were looking to meet local artists in order to develop experience for curating an exhibition and were open to all types of practices. The decision in supporting the group to connect with artists via a local studio instead of an open call for example, was informed by previous experience during my MA. For my MA project You Are Artists, I am Curator I advertised for artists via an online open call which meant that it reached a huge number of artists spread nationally. Whilst there was a great variety of applications, most of the artists lived some distance away and so communications were predominantly conducted online, presenting little opportunity for face-to-face time between the curators and artists. As this project was hoping to explore commissioning, it seemed logical to network with local artists who were able to participate in a quality collaboration with the group. From the advert with The Royal Standard, we had seven artists come in and work with the group during this ‘network’ phase. However, for the purpose of this thesis I have chosen to discuss three of the artist workshops; two of which were artists that ultimately were commissioned for the exhibition and one was not.

building networks

|

The first artist to deliver a workshop was Joseph Cotgrave, whom was undertaking an MA in Fine Art at Liverpool John Moore’s University at the time. Joe devised a brilliant workshop in which he collaborated with us to create an installation inspired by his previous piece Workspace (2015), which comprised of a fan inflating a large plastic form with items inside. Joe’s workshop began with a quick slideshow of his previous work. We then started making our own inflatable installation using a fan, plastic sheet, paint and selecting objects to place inside.

|

After Joe’s workshop, I discussed with the group what they thought about the experience. They particularly liked that Joe’s work used everyday materials that they see all the time. From items you could find at home - like the fan, paper, tape - or materials found on building sites seen all around Liverpool - like scaffolding, plastic and pallets. They felt it made his work accessible in that they can relate and understand these objects and materials, even though he transforms them. Joe also told the group that the materials he uses are inspired by his father who is a builder. Joe spent lots of time on building sites growing up and this “stuck with him”. I noticed the group really connected with this part of Joe’s explanation of the work - asking questions, clapping hands and telling Joe about their own families’ occupations. Similar to visiting The People’s Republic exhibition at the Museum of Liverpool, it is evident that the personal story underpinning the art was important to the group.

The most successful aspect of Joe’s installation from the groups perspective was that it moved. Leah said "It's like it was alive!". When the fan was switched on you could “watch it grow, and when you touch it, it bounces back and moves”. The group filled it with different objects like balls, feathers, paper, to see what would happen. They all seemed to really respond to the experimental aspect of Joe’s practice and surprisingly to me, did not seem to care that the installation did not ‘look like’ anything (a previous preoccupation with some group members). Here the group appeared to invest more in the process than the final product. “What would it like look like in the gallery?” I asked. “It could look quite good or it could look a right mess!” said Eddie, “they might look at the plastic and say, well I don’t give tuppance for that”. ‘They’ in this instance I assume is visitors of Bluecoat and Eddie touches on a great point; this installation was fun and engaging to make and is really all about the process. So, the question for me at this time was how do we convey the quality of this process to the audience so it moves beyond a giant piece of plastic that Eddie feels could be potentially overlooked or misunderstood by visitors?

The most successful aspect of Joe’s installation from the groups perspective was that it moved. Leah said "It's like it was alive!". When the fan was switched on you could “watch it grow, and when you touch it, it bounces back and moves”. The group filled it with different objects like balls, feathers, paper, to see what would happen. They all seemed to really respond to the experimental aspect of Joe’s practice and surprisingly to me, did not seem to care that the installation did not ‘look like’ anything (a previous preoccupation with some group members). Here the group appeared to invest more in the process than the final product. “What would it like look like in the gallery?” I asked. “It could look quite good or it could look a right mess!” said Eddie, “they might look at the plastic and say, well I don’t give tuppance for that”. ‘They’ in this instance I assume is visitors of Bluecoat and Eddie touches on a great point; this installation was fun and engaging to make and is really all about the process. So, the question for me at this time was how do we convey the quality of this process to the audience so it moves beyond a giant piece of plastic that Eddie feels could be potentially overlooked or misunderstood by visitors?

A few weeks later artist James Harper came in to work with the group. James, a member and a previous director of The Royal Standard, is an artist and also a curator. James began his workshop by sharing some of his previous work. For one of his pieces titled Pre-existing Form (2015-present) he had recreated a football, but instead of it being hard, it was soft and tactile. James explained that he made them so people can touch these in the gallery. The group passed them around and felt them, and discussed how touching art in galleries could be seen as breaking the rules; “that’s a good thing!” said Eddie.

Next James showed us a gif - a gif looks like short video clip which repeats itself over and over. Hannah, who perhaps has the most support needs in the group immediately spotted the gifs origin and blew James away with her pop culture knowledge. The gif was from the film Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and had been taken from the scene where the lucky golden ticket winners are inside the inventing room in awe of Willy Wonka’s unique (but wacky) ideas. Hidden under sheets - to keep his ideas top secret - is machinery moving suspiciously beneath them. James explained that his interest in the inventing room scene was because the machinery was hidden - it was a mystery. “Using this gif is a good idea because lots of people have seen the film and can relate to it.” said Leah.

The machinery in the film has inspired James to begin working with motors which formed the starting point for his workshop. James taught the group how to wire up a small circuit with a motor and a battery to which they attach painted panels to create a moving piece of artwork. What would our painted panels look like moving? How would they change? The group were so excited to see it all come together. James’ workshop was really successful in that he showed where his idea had come from. His work supported the group to think about autonomy in a new way, from personal autonomy to an autonomous machine, and the question of the day was; Can art take on a life of its own? The group made it very clear they wished to shortlist James to make the commission and are keen to work with him again.

Next James showed us a gif - a gif looks like short video clip which repeats itself over and over. Hannah, who perhaps has the most support needs in the group immediately spotted the gifs origin and blew James away with her pop culture knowledge. The gif was from the film Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and had been taken from the scene where the lucky golden ticket winners are inside the inventing room in awe of Willy Wonka’s unique (but wacky) ideas. Hidden under sheets - to keep his ideas top secret - is machinery moving suspiciously beneath them. James explained that his interest in the inventing room scene was because the machinery was hidden - it was a mystery. “Using this gif is a good idea because lots of people have seen the film and can relate to it.” said Leah.

The machinery in the film has inspired James to begin working with motors which formed the starting point for his workshop. James taught the group how to wire up a small circuit with a motor and a battery to which they attach painted panels to create a moving piece of artwork. What would our painted panels look like moving? How would they change? The group were so excited to see it all come together. James’ workshop was really successful in that he showed where his idea had come from. His work supported the group to think about autonomy in a new way, from personal autonomy to an autonomous machine, and the question of the day was; Can art take on a life of its own? The group made it very clear they wished to shortlist James to make the commission and are keen to work with him again.

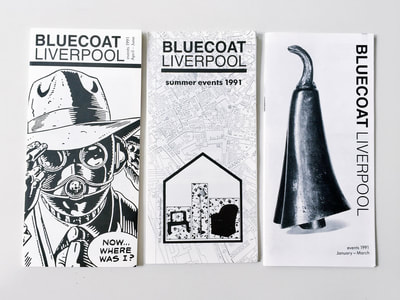

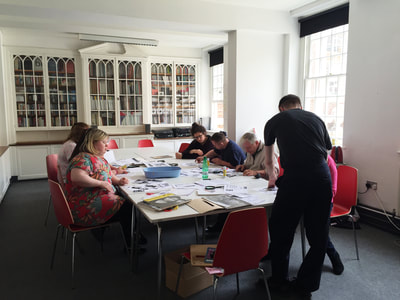

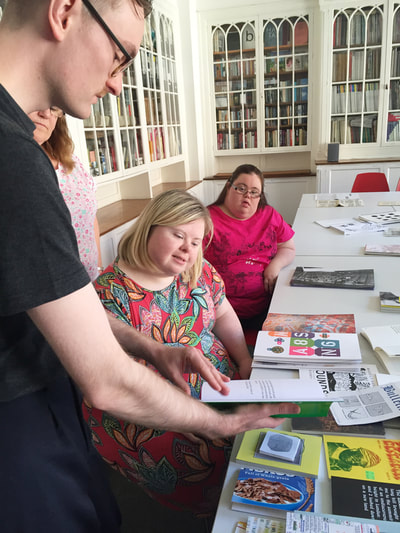

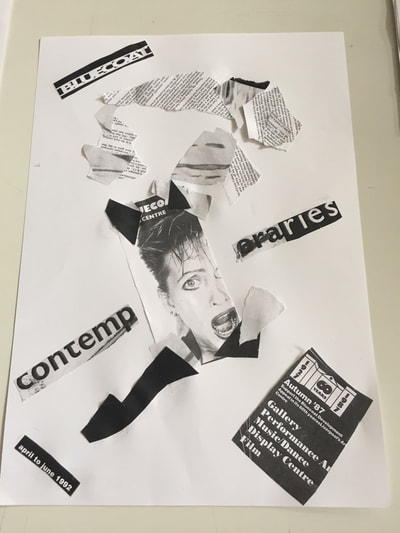

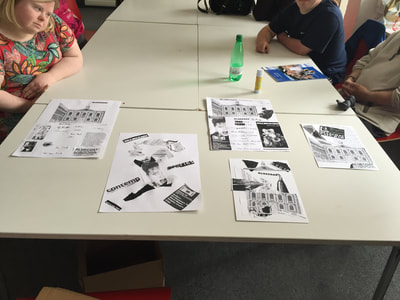

The final artist workshop I shall discuss is by Mark Simmonds who is a graphic designer, and so presented slightly different skills and approaches than the other workshop artists. Mark chose to host his workshop in Bluecoat’s library space, a room housing Bluecoat’s publications and ephemera, and also doubles as a meeting space. Mark’s workshop began with a question; What do you use books for? The group really surprised me and responded with some ingenious ways in which they use printed publications in their lives. Comics, programs, pop up books, games, literature, football pamphlets, textbooks, maps, the list went on! Fascinatingly, the group also responded by sharing with Mark their experiential relationships with books too. Eddie explains although he cannot read, he likes to buy books when he visits a new place. They act as a memory. Diana likes the smell of books and Hannah likes books which feel nice with textured paper. Mark was intrigued. Mark then opened up the cabinets and gave the group an activity; find a book with a picture of Bluecoat on, find a book that’s big, find a book you like the look of etc. The result was the workshop table full of diverse array of publications. The form of a book – its size and shape, paper stock, printing, cover and binding – as appose to just its contents an experience for the reader. The group thoroughly enjoyed the activity which supported them to explore the Bluecoat’s extensive archive.

Over lunch, myself and Mark photocopied the selected items so the group could create a collage with them, as Mark was interested in turning “old things into something new”. The group really enjoyed Mark’s approach to thinking broadly about books and asked me if he could help them make their own gallery publication. This was a great idea I thought, but it was contingent on funding I explained.

However, during the development of the artist network, I had begun to explore funding to enable the group to commission new art work and to support this idea of a gallery publication. Working closely with artists to commission art is seen as an empowering act for a curator as it represents a genuine act of authorship, therefore it seemed a fascinating route for the research to explore. Halton Speak Out took the lead in applying for the funds and they successfully won a Grants For Arts from Arts Council England. But as we would go on to explore, notions of authorship within the commissioning process are complicated.

selecting artists

A theme was in place, a network of artists was thriving, and we were in receipt of funding. But before we could interview and select artists, the group needed to decide on what sort of work they wanted to commission in the first place. Via the first research phase of the project, the curators had discovered an interest in exhibitions with stories and narratives, and from this decided their exhibition’s thematic starting point should be autonomy and independence. However, along with what the commission should address, they also needed to think about the potential physical form of the commission too. Their exhibition space The Vide in Bluecoat occupies a tall space reaching an impressive height of over twelve metres which is viewable from three multiple levels and perspectives. I supported the group to spend an afternoon working in the space, thinking about what type of art would best fit the environment. They identified the following key criteria:

1. Big! We think The Vide need a large piece of work.

2. Multi sensory/Interactive

3. Fits in with the autonomy theme

Using the above criteria, we invited three artists to be interviewed. We asked for no written application but wrote to the artists to advise them;

1. Big! We think The Vide need a large piece of work.

2. Multi sensory/Interactive

3. Fits in with the autonomy theme

Using the above criteria, we invited three artists to be interviewed. We asked for no written application but wrote to the artists to advise them;

|

We will ask you to recap what you did in your workshop with us.

We will ask you to pitch an existing artwork you have which fits our theme. We will ask you to pitch an idea for the commission. We would love to see lots of visuals; pictures, objects, plans, sketches, sounds and videos. Be as creative as you like! We will be considering how accessible your pitches are as part of our decision.

|

There is a considerable amount of literature on the inclusion of learning disabled people into interviewing processes. Self-advocates have continued to emphasise their right to influence as many aspects of their lives as possible, including choosing the staff who will work with them, and this was very evident during my time spent with Halton Speak Out[1]. Much of the literature on this topic however details case studies and the challenges to their inclusion. A frequently reported barrier is the challenges learning disabled people can experience grasping abstract concepts deemed necessary for a robust recruitment process. To give an example, Walker and Duffy (2001) reported that over 12 months learning disabled people were not involved in 42% of recruitments due to concerns about the level of responsibility or understanding required. Therefore it struck me as crucial to spend time on devising an interviewing process with the group which could potentially challenge previous ideas on how we ‘know’ or assess what a good candidate is.

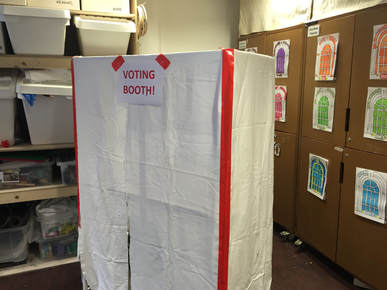

I spoke to the group about the best way to interview artists and we decided to practice by role playing scenarios and trying out methods. First we attempted to devise a scoring system, a way for the group to give and record their opinion. We tried marking the artist out of 10, but this did not work for all members of the group as the concept of number scale was too confusing. Next we tried a more simple version of thumbs up or thumbs down. This did work, but it was broad stroke and did not capture detail or nuance. It also did not mitigate against acquiescence, the “tendency to respond affirmatively regardless of a question’s content” (Carlson et al, 2002, p. 12) which can invalidate the response. Leah was the only group member who had previous experience in attending and conducting interviews. In her role at Halton Speak Out Leah often sits on interview panels with local learning disability district nurses to support their decisions on hiring new staff. Leah’s frustration was visible and she suggested we needed “a sheet with questions to think about, that’s how I’ve done it before”. After some heated discussions, we came up with a mixed method approach which incorporated Leah’s suggested of a question sheet (which admittedly I had shied away from because of concerns that it would be inaccessible), and an anonymous voting booth where each curator would vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ after each artist pitch.

I spoke to the group about the best way to interview artists and we decided to practice by role playing scenarios and trying out methods. First we attempted to devise a scoring system, a way for the group to give and record their opinion. We tried marking the artist out of 10, but this did not work for all members of the group as the concept of number scale was too confusing. Next we tried a more simple version of thumbs up or thumbs down. This did work, but it was broad stroke and did not capture detail or nuance. It also did not mitigate against acquiescence, the “tendency to respond affirmatively regardless of a question’s content” (Carlson et al, 2002, p. 12) which can invalidate the response. Leah was the only group member who had previous experience in attending and conducting interviews. In her role at Halton Speak Out Leah often sits on interview panels with local learning disability district nurses to support their decisions on hiring new staff. Leah’s frustration was visible and she suggested we needed “a sheet with questions to think about, that’s how I’ve done it before”. After some heated discussions, we came up with a mixed method approach which incorporated Leah’s suggested of a question sheet (which admittedly I had shied away from because of concerns that it would be inaccessible), and an anonymous voting booth where each curator would vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ after each artist pitch.

DIY Voting Booth

DIY Voting Booth

I decided to include a voting booth as I was acutely aware of the group dynamics at play. I had spent months working with the group at this point and had noticed that decisions were sometimes swayed by the more assertive members who offer their opinion first. To mitigate this, I suggested that we vote in secret before sharing our opinions with each other in an attempt to capture those individual ‘gut’ reactions to the artists. At the time, the EU referendum was fast approaching which was useful for the group in seeing the approaches in ‘everyday’ scenarios.

Now that a scoring system was in place, we needed to agree on how to decide whether the artists gave a ‘good’ interview. This proved even more difficult. Similarly to a study conducted by Kay and Ramsay (1999), I found that the group wanted to focus on the personal characteristics of the artists instead of their knowledge or skills. Whilst I agree that it was important for the group to like and get along with the artist they selected, it worried me that they were not taking into consideration the quality of the artist’s idea or their approach to pitching. Therefore, I suggested that a two-panel system could be helpful and we agreed to invite Adam Smythe, Bluecoat’s in-house curator, to help them interview. Each ‘panel’ focused on different aspects of the artists’ interview. The curators focused on assessing the artists character, accessibility and strength of concept, and Adam focused on evaluating skills, knowledge and feasibility of delivery. This is a great example of interdependency at play in the project. The curators sourced in Adams knowledge and experience to inform their decision. But crucially, it was still their decision to make not Adam’s.

Now that a scoring system was in place, we needed to agree on how to decide whether the artists gave a ‘good’ interview. This proved even more difficult. Similarly to a study conducted by Kay and Ramsay (1999), I found that the group wanted to focus on the personal characteristics of the artists instead of their knowledge or skills. Whilst I agree that it was important for the group to like and get along with the artist they selected, it worried me that they were not taking into consideration the quality of the artist’s idea or their approach to pitching. Therefore, I suggested that a two-panel system could be helpful and we agreed to invite Adam Smythe, Bluecoat’s in-house curator, to help them interview. Each ‘panel’ focused on different aspects of the artists’ interview. The curators focused on assessing the artists character, accessibility and strength of concept, and Adam focused on evaluating skills, knowledge and feasibility of delivery. This is a great example of interdependency at play in the project. The curators sourced in Adams knowledge and experience to inform their decision. But crucially, it was still their decision to make not Adam’s.

In order to best prepare the question sheet I decided to get advice from staff at Halton Speak Out. While open-ended questions are often preferred on the grounds of validity, the major disadvantage is that learning disabled people may find this too expansive and therefore confusing. In response, Halton Speak Out suggested including sub-questions along with the open-ended questions as a way to support the group to tackle the question. For example;

Question 1: Did you like their interview?

What you can see here is that the three sub-questions are in place to think about the broader question of ‘did you like the interview’. The sub-questions questions focus on the more behavioural, overtly observable characteristics such ‘did they talk to you?’, ‘did they have things to show you?’, instead of concepts that seemed abstract.

Next we tried out our system through role-playing an interview in an aim to make the experience more concrete and to develop skills (Johnson et al., 2012). Abi pretended to be a candidate for the commission and the group interviewed her for practice. For this mock interview, Abi had prepared a quick pretend pitch for the group. After Abi’s pitch, the group voted and we began discussing her interview using the prepared questions. It was interesting to see the faults they raised with Abi’s responses. When responding to one question, Abi slightly stumbled with her words – I could tell she was thinking on her feet grappling for the best way to explain herself. Eddie harshly critiqued this and said “she doesn’t know what she’s on about, I wouldn’t have her” and “it’s not good to stumble, you should be able to talk properly”. Leah and Tony got very offended by these comments. Leah pointed out that she feels we should not judge people on their talking abilities alone as she does not like it when people judge her on how she speaks. Diana and Hannah also agreed. On the other side of the coin, when Abi purposefully used inaccessible language in her interview, none of the group pointed it out. They seemed to be inconsistent in their feedback regarding language. I pointed this out to the group and asked if they noticed or whether it was their confidence. “I felt bad interrupting to say I didn’t get it” admitted Diana, “I sort of zoned out” remarked Eddie. Hannah also seemed really unsure and was very reliant on visual prompts to support any discussion.

Question 1: Did you like their interview?

- Was it easy to understand? Or Were you confused?

- Did they talk to you? Or Did they talk to Jade/Adam?

- Was it fun? Did they interact or have things to show you? Or Did they just talk and it was boring?

What you can see here is that the three sub-questions are in place to think about the broader question of ‘did you like the interview’. The sub-questions questions focus on the more behavioural, overtly observable characteristics such ‘did they talk to you?’, ‘did they have things to show you?’, instead of concepts that seemed abstract.

Next we tried out our system through role-playing an interview in an aim to make the experience more concrete and to develop skills (Johnson et al., 2012). Abi pretended to be a candidate for the commission and the group interviewed her for practice. For this mock interview, Abi had prepared a quick pretend pitch for the group. After Abi’s pitch, the group voted and we began discussing her interview using the prepared questions. It was interesting to see the faults they raised with Abi’s responses. When responding to one question, Abi slightly stumbled with her words – I could tell she was thinking on her feet grappling for the best way to explain herself. Eddie harshly critiqued this and said “she doesn’t know what she’s on about, I wouldn’t have her” and “it’s not good to stumble, you should be able to talk properly”. Leah and Tony got very offended by these comments. Leah pointed out that she feels we should not judge people on their talking abilities alone as she does not like it when people judge her on how she speaks. Diana and Hannah also agreed. On the other side of the coin, when Abi purposefully used inaccessible language in her interview, none of the group pointed it out. They seemed to be inconsistent in their feedback regarding language. I pointed this out to the group and asked if they noticed or whether it was their confidence. “I felt bad interrupting to say I didn’t get it” admitted Diana, “I sort of zoned out” remarked Eddie. Hannah also seemed really unsure and was very reliant on visual prompts to support any discussion.

The day of the interviews arrived. The first artist to be interviewed was Becky Peach, an artist with a breadth of knowledge in the field of Printmaking. For her workshop, Becky focused on her piece titled Do Touch (2015). Do Touch is a sculpture made from Perspex. No larger than an A3 sheet of paper, there are nine separate parts, each made using a laser cutter and screen printed onto using process colours; Cyan, Magenta and Yellow. The sculpture seems to follow a similar principle to the children’s construct game K’NEX, in that each piece can slot together to create innumerable configurations. The works title Do Touch essentially acts as instructions, urging the audience to break with the conventions and etiquette of the gallery space. For the workshop, the group began by screen printing shapes onto cardboard. This is a new skill for most of the group and they all discussed about what hard work it was! After printing the designs, the group were asked to cut out shapes and think about how they would slot together. The group were engrossed in playing with their work. Everybody made different configurations and played with each other’s artworks.

Becky began her interview by recapping her workshop by showing the group their cardboard versions of Do Touch, whilst talking through how they made them. This went down well with the group. Becky then began to discuss her idea for the commission itself. Responding to the group’s request for an inclusive pitch, Becky had made a mood board. This mood board was a collage of other artist’s work who had inspired her, but whilst this gave myself and Adam a sense of her conceptual approach to the commission, the group were very confused by the mood board and assumed it was all of Becky’s previous work. This led some awkward conversations for Becky trying to explain the purpose a mood board, to which the group seemed to disconnect. Becky moved on and showed the group some drawings for commission idea. Becky was keen to produce a piece of work which explored different textures in the space, such as artificial grass, perspex and mirrors. The group liked this idea but seemed confused, despite her drawings, on the physical form it would take. After the interview, we chatted about Becky’s ideas with our prepared questions to guide us. It became clear that whilst the group really liked her and her overall approach to art making, they did not understand the commission and for them, they felt it was not interactive enough.

Becky began her interview by recapping her workshop by showing the group their cardboard versions of Do Touch, whilst talking through how they made them. This went down well with the group. Becky then began to discuss her idea for the commission itself. Responding to the group’s request for an inclusive pitch, Becky had made a mood board. This mood board was a collage of other artist’s work who had inspired her, but whilst this gave myself and Adam a sense of her conceptual approach to the commission, the group were very confused by the mood board and assumed it was all of Becky’s previous work. This led some awkward conversations for Becky trying to explain the purpose a mood board, to which the group seemed to disconnect. Becky moved on and showed the group some drawings for commission idea. Becky was keen to produce a piece of work which explored different textures in the space, such as artificial grass, perspex and mirrors. The group liked this idea but seemed confused, despite her drawings, on the physical form it would take. After the interview, we chatted about Becky’s ideas with our prepared questions to guide us. It became clear that whilst the group really liked her and her overall approach to art making, they did not understand the commission and for them, they felt it was not interactive enough.

Next to be interviewed was James Harper. James began by taking the group through a presentation, which ‘told the story’ of his first workshop, his artistic inspiration, and his idea for the commission. His presentation began by showing the group a series of photographs he had collected of found items hidden under sheets like cars, trees and machinery. James then shared the Charlie and The Chocolate Factory gif again with the group and discussed the link to the ‘inventing room’ and James proposed perhaps the gallery is also like “an inventing room of sorts?”. It appeared that James was using these examples to outline his conceptual framework to group; things that are hidden. James then went to discuss his commission in more detail. Inspired by the hidden mechanism in Willy Wonka’s invention room and proposed creating a large mechanical installation covered by a sheet which would hang in The Vide. Responding to themes of autonomy and independence, this mechanical piece would be controlled through a series of switches. The audience would have choice and control over how it moves. The interactive and bizarre nature of his idea was a big hit. Leah straight away asked if we could add sounds and Diana quickly spotted that children would find this really fun.

What I noticed James did well, was using storytelling techniques to make it accessible such as framing his conceptual framework as; “a long time ago I was inspired by…”. He also included lots of images and videos, as well as making a model of the installations internal structure and a plan to scale and bringing in materials for the group to feel and touch. James had also been in touch with one of Bluecoat’s gallery technicians to go over plans for feasibility which Adam was pleased with. When James left, the group knew exactly what the work was and were able to describe it back to me. They were visibly excited – clapping, shouting and laughing.

Finally, we interviewed Joseph Cotgrave. Joe also began with a slideshow where he recapped his previous workshop with the group and his inspiration behind his work. During this part of the interview, I did notice that it was rather muddled and he slipped into using lots of jargon. I could see Hannah and Diana becoming distracted. Joe brought along some sketches and had drawn his idea to the blueprint of The Vide space which was great to see and the group were impressed. Joe’s idea for the commission was a large inflatable installation which the audience could walk inside. This idea is inspired from his previous workshop where the group made a smaller inflatable installation with a fan and he was interested in the construction of spaces and environments.

After Joe left, the group were a bit confused and struggled to describe the artwork back to me. How can you walk in it? What would it looks like finished? And then questions around its accessibility crept in. Leah asked about wheelchairs and Diana and Eddie didn’t think the idea would work at all. Diana also believed some people might be scared to go in it and wondered how you’d get out the other side. These were all astute observations. I also doubted whether the gallery was actually big enough for this piece but also questioned whether it spoke to the groups theme of autonomy very well either. Adam also had many questions about the inflatable structure in terms of health and safety and suggested we got a budget breakdown as he questioned whether something so ambitious could be achieved on budget.

After Joe left, the group were a bit confused and struggled to describe the artwork back to me. How can you walk in it? What would it looks like finished? And then questions around its accessibility crept in. Leah asked about wheelchairs and Diana and Eddie didn’t think the idea would work at all. Diana also believed some people might be scared to go in it and wondered how you’d get out the other side. These were all astute observations. I also doubted whether the gallery was actually big enough for this piece but also questioned whether it spoke to the groups theme of autonomy very well either. Adam also had many questions about the inflatable structure in terms of health and safety and suggested we got a budget breakdown as he questioned whether something so ambitious could be achieved on budget.

|

SCENE 1: WHAT ABOUT JOE?

The group are in the Makin Room discussing the interviews and who they feel gave the best pitch and would be the best candidate for the commission. LEAH: I think James did the best. I didn’t get Joe’s at all, and I don’t think it’s very accessible. DONNA: Hannah, did you understand Joe’s idea? HANNAH: …mmm, yeah DONNA: Can you explain what it was? HANNAH: … no… like, Charlie and the chocolate factory? DONNA: That was James’ idea, did you like that one? HANNAH: yes, yes!!! DIANA: You ok Tony? [Tony says nothing, but has his face covering his hands] DIANA: What’s up mate? EDDIE: …You alright Tony lad? [Tony still doesn’t respond, but further covers his face] ABI: [To Jade] I think he’s upset about Joe and the feedback about him… JADE: Is everything alright To? Would you like to step outside and have a chat? TONY: Yeah, you’re all being mean about Joe. |

In this scene we see Tony’s reaction to the group’s critique of Joe’s interview. Tony really got on with Joe and had sparked a great rapport during his workshop, but I - and the group - was still very taken aback by Tony’s reaction. It was unexpected. I had a chat about this with Tony one-on-one and explained we all really liked Joe and the group was not being mean about him as a person, but simply questioning whether his idea was the best choice for the show. This is where the ‘thumbs up’ or ‘thumbs down’ approach to interviewing proves inadequate. What also struck me is throughout supporting the group to develop a network of artists is, what happens when those relationships do not fulfil the requirements of the exhibition? It becomes hard to sever ties and exclude an artist for being involved when they have input so much already. These relationships need to be carefully managed and in hindsight I did not anticipate the potential impact on the group to ask them to exclude somebody. This can be understood in terms of relational accountability. Relationships essentially underpin participatory action research approaches, as for the most part, relationships describe individuals contributing as partners who are co-investigators in addressing questions or issues. Shawn Wilson, an aboriginal and indigenous scholar established the term ‘relational accountability’ which he describes as research that is both “based in a community context” and “demonstrates, respect, reciprocity, and responsibility as it is put into action” (2008, p.99). Relational accountability encourages researchers to look at the “entire systems of relationships as a whole” (Reimer, L., Schmitz, C. Janke, M. et al., 2015, p.47) in their inquiries, which I did not do so well during the interviewing process. Instead of taking into account all relationships, I focused on the relationship between the curators and successful candidate only.

After this conversation, it was evident that the majority of the group wished to select James. Therefore, I needed to think carefully about how to frame this to Tony who I knew would feel disappointed. The group needed time to think and cool off, so it was not until a week later we revisited the interviews and made our final decision.

The following week I advised the group it was time to make their final decision, and we began by discussing each candidate one at a time. I did this by showing the group photographs of artists, as well as their artworks, documentation of their workshop and any items from their interviews. This helped differentiate candidates during discussions, as that one problem experienced during the selection process was remembering candidates and distinguishing between them when a decision was required. I read out the results of the votes, and James had won[2]. Tony was still a little hesitant and remained quiet during the conversation. However, Diana shared that she had actually voted for Becky, but realised “I don’t think it makes good sense for the show now” which Tony clearly appreciated. The voting booth seemed to help with this final conversation as it allowed the other members of the group to move away from personal critique to discussing the ‘objective’ votes; “It needs to be a group decision” said Leah, “Let’s go with who got the most votes”. With all taken into account, the group were delighted to select James and we wrote to him that day to tell him the good news, as well as informing the other two candidates along with some feedback.

developing the commissions

Just three weeks later, James and Mark joined us for their first workshop with the group. As part of development the commissioning, both artists had been funded to spend five full days each working with the group in order to input and develop the commission. I began this workshop by facilitating a PATH. After a couple of weeks off for holidays, I felt this would be useful for the group to get up to speed again, and also useful for James and Mark to experience a person-centred tool in action and the groups approach planning around the show. PATH, is a person-centred tool which breaks down the steps needed to achieve a goal. Helen Sanderson explains; "PATH is there when a situation is complex and will require concerted action, engaging other people and resources, over a longish period in order to make an important vision real" (Helen Sanderson Associates, 2017b). The developers of PATH, Jack Pearpoint, John O`Brien and Marsha Forest suggest;

|

PATH is a way for diverse people, who share a common problem or situation to align… their purposes… their understanding of their situation and its possibilities for hopeful action…their action for change, mutual support, personal and team development and learning (ibid).

|

I have seen this tool work wonders in self-advocacy contexts. Many years ago Leah taught me how to facilitate PATH’s when I volunteered at Halton Speak Out and she still uses them in her own life planning. To reflect the task we were trying to break down - the exhibition - I slightly adapted the titles from the typical PATH. The titled I used were Now, Who can help?, Building Strengths, Half Way Goal!, Final Steps, The Exhibition...

First I asked the group what their dream for the exhibition was, what do they imagine? “Lots and lots of people!” said Diana, “it’s really good and people like it” said Eddie, and “our names are up there” he continued. All these were written down and we talked about the effects we wished the show to have. Next I said, “But how will we get to this dream? Let’s think about Now; what do we know now and what we can do right now”. The group looked blank. I asked them to think about what we have already done, the places we have visited and Tony said, “seeing other galleries and what they do”. We talked about how this was a type of research and gave us experience of seeing lots of different types of exhibitions, ‘some weren’t very good’ said Eddie. “That’s ok!” I said, “but we need to think about why”. The next step was Who Can Help and the group found this one very easy to answer, in fact I could hardy hear through all the names they were shouting out! The group were able to identify all the different types of support - from family, friends and support workers, to organisations like Ella and Blue Room, to artists, media figures and even celebrities! The Building Strengths and Half Way Goals were quite tricky steps for the group. The group were not able to think of skills they were lacking. I asked if they knew what marketing was and whether a strength to be built could be how to get people to come to our show. We talked about artists’ interviews and making the commissions as our Half Way Goals, and The Final Steps included installing the work, inviting people to see the work, organising a party, perhaps doing tours.

First I asked the group what their dream for the exhibition was, what do they imagine? “Lots and lots of people!” said Diana, “it’s really good and people like it” said Eddie, and “our names are up there” he continued. All these were written down and we talked about the effects we wished the show to have. Next I said, “But how will we get to this dream? Let’s think about Now; what do we know now and what we can do right now”. The group looked blank. I asked them to think about what we have already done, the places we have visited and Tony said, “seeing other galleries and what they do”. We talked about how this was a type of research and gave us experience of seeing lots of different types of exhibitions, ‘some weren’t very good’ said Eddie. “That’s ok!” I said, “but we need to think about why”. The next step was Who Can Help and the group found this one very easy to answer, in fact I could hardy hear through all the names they were shouting out! The group were able to identify all the different types of support - from family, friends and support workers, to organisations like Ella and Blue Room, to artists, media figures and even celebrities! The Building Strengths and Half Way Goals were quite tricky steps for the group. The group were not able to think of skills they were lacking. I asked if they knew what marketing was and whether a strength to be built could be how to get people to come to our show. We talked about artists’ interviews and making the commissions as our Half Way Goals, and The Final Steps included installing the work, inviting people to see the work, organising a party, perhaps doing tours.

The group really enjoyed and responded to doing PATHs and although they were undertaking a planning and memory exercise, I always found the group to be energised after doing one. James and Mark took a back seat during the PATH and appeared to be intrigued by the process. What I noticed from doing PATHs regularly with the group is often they tended to forget about interpretation. They rarely factored in that they would need to create things to help the audience understand the exhibition. Therefore during this particular PATH, I decided to prompt a discussion about this. “How do you like to be interpreted?” asked Diana to James. James laughed. “Well, a curator has never asked me that before!”. He explained he was very happy and relieved that Diana had asked that, as it’s “not very nice when curators explain your work without you being involved”. “Oh no” Eddie said, “we won’t be doing that!”. Eddie then began describing to James the video in the Matisse in Focus exhibition. “I’d like to do something like that”. James agreed that this was a really good way to tell the audience about his work, Mark agreed too. Mark suggested it might be fun to ask if we can film at the printers to show people how the book was made. The group loved this idea. They then all discussed, without me saying a word, different things they could film, who could help, and what effect this could have on the audience. James said that maybe we could show some of these films on old TV’s, perhaps to build on the ‘factory’ feel of his piece. “I like that” said Leah.

Observing this conversation unravelling was exhilarating for me as both a facilitator and researcher. I felt that this moment encapsulated much of what I hoped this project could achieve; collaborations between the artist and curator that begins to re-think the traditional curated exhibition. After the PATH, James took over the session to begin working with the group to get their thoughts on the commission. James asked to draw around each of the curators, to use their outline to make aspects of the artwork. The group happily obliged and after James had done the drawings, they decided to take them into the gallery to see how big they were in the space.

At the next workshop a couple of weeks later, James wanted to begin by sharing some swatches of fabric with the group, so he could begin properly planning the material to cover his sculpture. However, the group had other ideas.

Observing this conversation unravelling was exhilarating for me as both a facilitator and researcher. I felt that this moment encapsulated much of what I hoped this project could achieve; collaborations between the artist and curator that begins to re-think the traditional curated exhibition. After the PATH, James took over the session to begin working with the group to get their thoughts on the commission. James asked to draw around each of the curators, to use their outline to make aspects of the artwork. The group happily obliged and after James had done the drawings, they decided to take them into the gallery to see how big they were in the space.

At the next workshop a couple of weeks later, James wanted to begin by sharing some swatches of fabric with the group, so he could begin properly planning the material to cover his sculpture. However, the group had other ideas.

|

SCENE 2: BUT WE CHOSE HIM?

Artist James and the curators are gathered around a table in the Makin Room. Today is the second workshop with James, they’re discussing the plans for the commission. TONY: Lights would be good. Like, moving lights… [interrupted] DIANA: Yeah, lights! TONY [continued]: …like a disco JAMES [hesitant]: Oh right… um… well… [interrupted] EDDIE: That does sounds good JAMES [continued]: Well, I don’t think lights were a part of my original pitch if you remember? My work looks at movement. EDDIE: Oh right [The room goes quiet and everyone looks at James] JAMES: It’s an interesting idea, it’s just I’ve never really worked with lights DIANA: Awww he doesn’t know, never mind JAMES: I mean, I could find out but… I’m just not sure it will look right, it’s not really my style EDDIE: Lights would get people’s attention JAMES: ….yeah… um JADE: Maybe we should leave the idea of lights with James and give him time to think about it. Let’s refocus and chat about the fabrics James has brought in to show you? [Diana turns to Jade] DIANA: But we like lights and we chose him? |

The room was tense, and all eyes were on me. In this vignette, we get a sense of the complexities unfolding when commissioning artwork, which here, circle around autonomy and authorship. Whilst Diana was the only one to explicitly voice her confusion surrounding the authorial boundaries of the commission at that time, she certainly was not alone. After all, the curators had worked hard for five months to develop an exhibition theme, secure funding and network with artists. Understandably for them, and I suppose for many curators in a similar position, it was difficult to relinquish control. And so for us, the concept of autonomy was explored not just in the exhibition’s theme but also through the curatorial processes themselves.

From this scene, I feel it is very evident how torn James was. On the one hand he appears to want to please, or at least, appease the curators; “I mean, I could find out…” and “it’s an interesting idea”. However, I believe this is politeness. It was only the third time James had worked with the group and I suspect he wasn’t yet sure how to say no to them. In this scene Diana directly points out to James that they selected him; “we chose him”, and I wonder whether the subtext here is that their opinion is therefore of importance. Writer and Editor of Art Flux Journal Anton Vidokle discussed this his piece Art without Artists (2010). Vidokle asserts the importance of artists to have what he describes as “sovereignty”. “By sovereignty” Vidokle writes, “I mean simply certain conditions of production in which artists are able to determine the direction of their work, its subject matter and form, and the methodologies they use—rather than having them dictated by institutions, critics, curators, academics, collectors, dealers, the public, and so forth” (ibid). Furthermore, is this “sovereignty” described also crucial in underpinning the very freedom of art as expression? In the scene, James does eventually express his reluctance in their suggestion of including lights into his commission; “Well, I don’t think lights were a part of my original pitch” and “it’s just I’ve never really worked with lights” indicating his desire to keep true to his vision for the piece and his artistic style, or asserting his artistic ‘sovereignty’.

So, whilst a brief moment in the overall project, for me this scene cuts to the heart of some really crucial issues with my work which circle around complexities of autonomy, interdependence and authorship. Here, the curators are not seeing decision-making as a shared responsibility and seem to suggest that the act of selection has given them autonomy over the commission. I also feel that this scene reveals something about risk taking. From this scene we can see all sorts of risks playing out; either the curators are taking risks in allowing the artist to do it his own way despite their suggestions and overarching vision for the show, or the artists takes on board the curators comments and risks the art by comprising his practice and approach. Art collector Dennis Scholl comments;

From this scene, I feel it is very evident how torn James was. On the one hand he appears to want to please, or at least, appease the curators; “I mean, I could find out…” and “it’s an interesting idea”. However, I believe this is politeness. It was only the third time James had worked with the group and I suspect he wasn’t yet sure how to say no to them. In this scene Diana directly points out to James that they selected him; “we chose him”, and I wonder whether the subtext here is that their opinion is therefore of importance. Writer and Editor of Art Flux Journal Anton Vidokle discussed this his piece Art without Artists (2010). Vidokle asserts the importance of artists to have what he describes as “sovereignty”. “By sovereignty” Vidokle writes, “I mean simply certain conditions of production in which artists are able to determine the direction of their work, its subject matter and form, and the methodologies they use—rather than having them dictated by institutions, critics, curators, academics, collectors, dealers, the public, and so forth” (ibid). Furthermore, is this “sovereignty” described also crucial in underpinning the very freedom of art as expression? In the scene, James does eventually express his reluctance in their suggestion of including lights into his commission; “Well, I don’t think lights were a part of my original pitch” and “it’s just I’ve never really worked with lights” indicating his desire to keep true to his vision for the piece and his artistic style, or asserting his artistic ‘sovereignty’.

So, whilst a brief moment in the overall project, for me this scene cuts to the heart of some really crucial issues with my work which circle around complexities of autonomy, interdependence and authorship. Here, the curators are not seeing decision-making as a shared responsibility and seem to suggest that the act of selection has given them autonomy over the commission. I also feel that this scene reveals something about risk taking. From this scene we can see all sorts of risks playing out; either the curators are taking risks in allowing the artist to do it his own way despite their suggestions and overarching vision for the show, or the artists takes on board the curators comments and risks the art by comprising his practice and approach. Art collector Dennis Scholl comments;

|

We commission works because it’s very adventurous. It’s so much more involved than going to a show and saying ‘I’ll take the third one from the left’. But it’s also very hard, it’s complex and it’s very risky: Sometimes you can get the most inspired work ever; other times it doesn’t work out so well. (Buck and McClean, 2012, p. 35).

|

The risk that Scholl discusses here is in relation to the ‘unknown’, as commissioning work means you can never really anticipate the final result. Similarly, Maria Frisa (2008, p.172) writes;

|

As a curator you have to take risks, because you have to put your ideas to the test; by following an intuition and constructing a project which only becomes a reality when it is finally complete. It is at this point that it is subjected to the judgment of others—and this is the point of curation.

|

When thinking about risk taking in self-advocacy contexts, often the lives of learning disabled people are incredibly risk averse. There have been a number of studies, particularly around the time of the personalisation agenda, which discuss the dichotomy of enabling risk - through autonomy and choice - whilst still maintaining safeguarding duties (Fyson, 2009; Close, 2009; CSCI, 2008). As the Department of Health outlines; “The goal is to get the balance right moving away from being risk averse while still having appropriate regard for safeguarding issues” (DH, 2008, p. 23). For example in 2012, The Joseph Rowntree Foundation conducted large study The Right to Rake Risks, and they suggest one of the key reasons for this risk averse approach has more to do with implications for the accountability of the care providers than individuals. Similarly, a report by Sarah Carr on behalf of the Social Care Institute for Excellence also documented risk aversion on the part of social care practitioners. It found genuine concern for the safety of groups seen as ‘vulnerable’, but often it “is based on assumed or perceived risk solely on the part of the practitioner” (2010, p. 5). Therefore self-advocates and their supporters argued that ‘risk’ is often perceived negatively by people using services because it is “used as an excuse used for stopping them doing something” (Glasby, 2011, p.1). Doug Paulley, a disability activist who lives in a residential home, refers to as this as ‘Careland’. “In Careland” he explains, “there are different rules - you are not expected or allowed to do things that might hurt you or might risk your safety even if that ‘safety’ means risking your own independence and wellbeing” (Faulker, 2012, p.11). But risk needs to be shared between the individual taking the risk and the system that is trying to support them. This should be equally as personalised.

I talked about risk with the group, both in regards to the commission and to their own lives. Leah one of the curators on this project talked a lot about her frustrations in not being allowed to try things out and make mistakes. She talks about having to go on a training course in order to support her engagement to her boyfriend; “everyone’s so scared that we don’t know what we’re doing”. Ideas of risk, choice and control carried over into the curation of other works for Leah. She was instrumental in including the piece by artist Alaena and worked closely with her to produce the interpretation for the show about this work. Leah describes “I think these paintings are celebrating mistakes and accidents, something if you’ve got a learning disability you’re not allowed to do”.

In addition to risk, Scene 3 also flags issues of authorship. We see the curators pushing their vision for the artwork, the idea of including lights, onto James. As discussed in Act 1: Prologue, the act of commissioning art is nothing new and the relationship between the artist and commissioner is well discussed in the literature and often focuses on authorship. Whilst the curator’s role in shaping commissions is widely recognised, Vidokle (2010) warns that the curators curatorial themes and “authorial claims” should not take precedence over the artists’ work. He believes that such practices run a serious risk of undermining the agency of artists and diminishing the space of art all together. It seems the role of curator has become so entwined with connotations of knowledge, status and power that perhaps their ‘authorial claim’ can become dominant, because how would an artist challenge it? Through their role curators wield considerable power and play a crucial part in the subscription process. Authorship is therefore tied into the careful negotiation of power in the commissioner/artist relationship. This has even brought into debate whether the term curator is becoming outdated. In conversation with fellow curator Nato Thompson, Michelle White proposes that perhaps the very term curator does not account for the delicate collaborations at stake in the role or other subtle forms of power;

In addition to risk, Scene 3 also flags issues of authorship. We see the curators pushing their vision for the artwork, the idea of including lights, onto James. As discussed in Act 1: Prologue, the act of commissioning art is nothing new and the relationship between the artist and commissioner is well discussed in the literature and often focuses on authorship. Whilst the curator’s role in shaping commissions is widely recognised, Vidokle (2010) warns that the curators curatorial themes and “authorial claims” should not take precedence over the artists’ work. He believes that such practices run a serious risk of undermining the agency of artists and diminishing the space of art all together. It seems the role of curator has become so entwined with connotations of knowledge, status and power that perhaps their ‘authorial claim’ can become dominant, because how would an artist challenge it? Through their role curators wield considerable power and play a crucial part in the subscription process. Authorship is therefore tied into the careful negotiation of power in the commissioner/artist relationship. This has even brought into debate whether the term curator is becoming outdated. In conversation with fellow curator Nato Thompson, Michelle White proposes that perhaps the very term curator does not account for the delicate collaborations at stake in the role or other subtle forms of power;

|

The term cultural producer, aside from the particular conditions of our moment, is a healthier or more honest way to articulate the contemporary role of the curator. It acknowledges the complexity of the collaboration that has to happen when something like an exhibition is organized or a project is carried out, which involves, as you said, a much more complex institutional web of financial as well as physical logistics from the relationship of collectors, patrons, boards of trustees to the possibilities of display space. It is certainly beyond the simple curator/artist dichotomy. But at the same time, in working on site-specific projects or exhibitions with living artists where collaboration is essential to produce meaning, I have found myself questioning the boundaries of my involvement in the aesthetic and conceptual production. So, I wonder, are there risks in assuming this more egalitarian position as producer? (White, 2008)

|

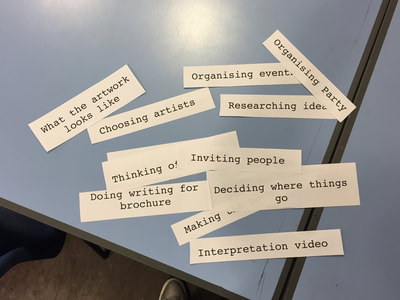

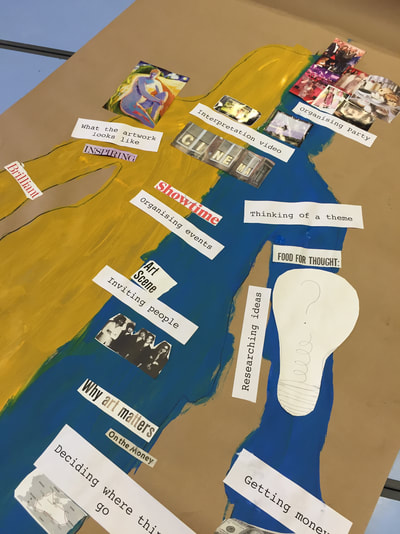

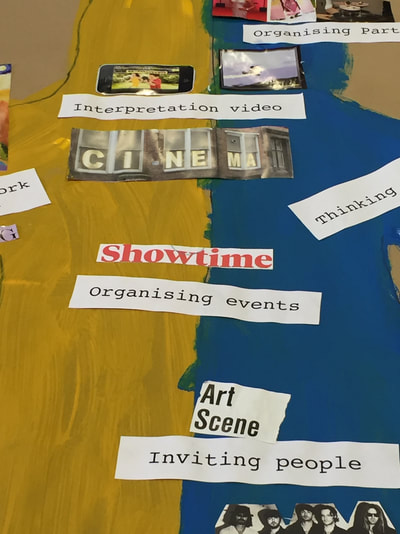

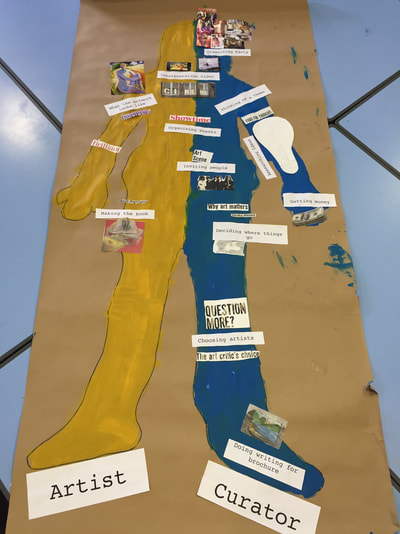

Following the workshop with James, I decided to work with the group to think more closely about the relationship between an artist and curator as much was at stake. To support the group to self-define their role in producing the exhibition I suggested we make our own ‘Auto Agent’, who affectionately got dubbed by the group as Auto Agent Bob (images below). To create Auto Agent Bob I asked the group to make a large outline of a person who was divided in half down the middle; one half to represent the artist and the other half the curators. I printed out labels for the group which described tasks in making an exhibition such as ‘choosing artists’, ‘getting money’ and ‘making the artwork’. I then asked the group to think of where each labels should go on Auto Agent Bob, the artist’s side or curator’s side? Everyone grabbed a label and in less than 30 seconds, and not to my surprise, the curator’s half of Auto Agent Bob was full whilst the artist side of Auto Agent Bob was bare. In other words, the group clearly felt like all of the decisions in the exhibition were theirs to make. “That’s interesting” I said, “Let’s do it again but this time pretend we are the artists and not the curators”. This time round no one wanted to place down a label first. “Who makes the artwork?” I asked. “Oh yeah”, said Eddie, “the artists do!”. Tony placed his label of “making the artwork” on the artist side. Slowly we went through each label and looked at the task from the perspective of artists. This time round many shared tasks emerged, one of which was interpretation[3]

Following this activity I suggested we use this learning to draw up Decision Making Agreement. In this document we list the important decisions to be made in regards to the exhibition, how everyone should be included, but crucially, who gets the final say. This provides guidance we can refer back to when tensions emerge around agency and authorship. I have developed these type of agreements with self-advocates in the past and they are commonly used as a person-centred planning tool (Helen Sanderson Associates, 2017). Decision Making Agreements aim to break down information into three easy sections: ‘important decisions in my life’, ‘how I must be involved’ and ‘who make the final decision’, to “help people to reflect on how decisions are made and who is making them” (ibid).

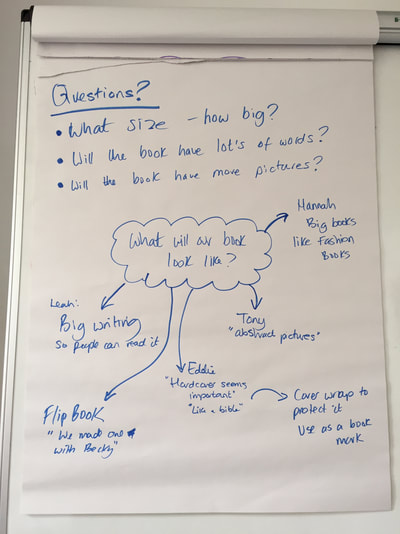

Simultaneously as James’s commission was developing the group were also working with Mark to create a gallery publication. Mark had been attending some of James’ workshops in an aim to learn about the exhibition and the work in it to inform what form the publication could take. Early on it was decided that the publication would not be overly textual, but instead explore other ways to produce a gallery publication. This was because four out of the five curators could not read or write independently, they felt that a textual interpretation of the exhibition would not make sense. Instead, Mark suggested they focus on the experiential dimension of books and alternate ways of ‘reading’. This view that books can be ‘read’ in many different ways is well explored amongst artists, who have long understood the potential of the book form to do more than just display information.

Simultaneously as James’s commission was developing the group were also working with Mark to create a gallery publication. Mark had been attending some of James’ workshops in an aim to learn about the exhibition and the work in it to inform what form the publication could take. Early on it was decided that the publication would not be overly textual, but instead explore other ways to produce a gallery publication. This was because four out of the five curators could not read or write independently, they felt that a textual interpretation of the exhibition would not make sense. Instead, Mark suggested they focus on the experiential dimension of books and alternate ways of ‘reading’. This view that books can be ‘read’ in many different ways is well explored amongst artists, who have long understood the potential of the book form to do more than just display information.

|

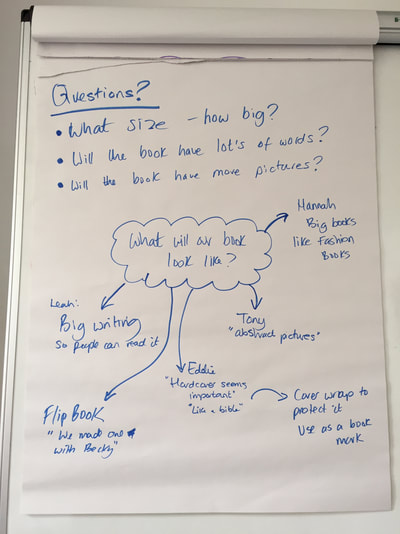

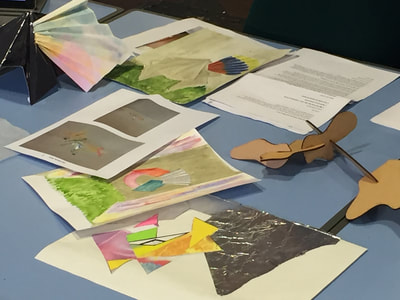

During Mark’s next workshop he supported the group to think about movement. “Books don’t move!” laughed Diana! “Of course they do” replied Mark, “look…”, Mark began flipping through a book and the groups watched the pages turning. “You can’t really read a book without turning pages”. The group then went on to explore flip books, books with a series of pictures that vary gradually from one page to the next, so that when the pages are turned rapidly, the pictures appear to animate. They practiced the technique with post it notes and then went on to create more elaborate flip books once the technique was mastered. In another workshop, Mark brought along a wide range of paper swatches for the group to feedback on colour, paper weight and shine. Everyone got to pick a colour and Mark talked through the different sizes of books the printers could offer.

|

The first draft Mark produced for group received a tepid response. I suspect this was because it was not as playful as the previous flip books and that Mark has used cheap paper and binding for draft purposes. “I don’t like this paper” Tony commented. “Yeah I get that, it’s just cheap paper to give you an overall idea of the book” Mark explained. Normally when producing a draft Mark would use cheap materials to keep costs down, however when producing a book that is intended to be ‘read’ through its physical form such as the paper qualities, using different materials meant the draft became abstracted. This proved difficult for the group. In the future Mark worked to provide drafts that were as close to the final piece as possible in order to support the group to give more informed feedback. Aside from the paper issues, in this first draft Mark introduced the idea of including the question “what do you use books for?”, which was the question he originally posed to the group at their first meeting. However, as the group made it clear they didn’t want the book to be textual, Mark proposed making it very hard to read this question for ‘able reading’ audiences through splitting up the words by putting a letter on each page. This would mean the audience would focus on the patterns and shapes of letters instead of what they said. This received mixed reactions from the group. Some members did not understand the concept, whilst others did and loved the idea of ‘complicating reading’.

|

SCENE 3: IT’S COMPLICATED

After Mark’s workshop, I discuss with the group again what they thought of his idea of ‘complicating reading’. TONY: I think it’s good DIANA: Yeah, it’s funny. They can’t read like us! EDDIE: …Well I don’t like it. It’s complicated and people won’t know where they’re at ABI: I think it’s a really clever idea DIANA: Yeah, a clever idea! JADE: Leah, Hannah, what do you think? HANNAH: It’s nice, nice colours DONNA: Jade is asking about the letters and the question HANNAH: Yeah it’s letters [looks confused] DONNA: I’m not sure Hannah quite understands this one… JADE: Ok [makes notes] How about you Leah? LEAH: Yeah I like it. But I understand where Eddie is coming from, will people get the idea from the book? I only got it when you explained it to me. JADE: That’s a great point. Something to ask Mark I think. Since there’s a bit of a split decision here, who will get the final say on including this in the book? DIANA: Don’t know. LEAH: We need to check the contract. EDDIE: Oh yeah! We did that. Fair enough I suppose, we can only tell him we don’t quite get it and it’s up to him to make it work. |

In this scene we see the group discussing concerns over Mark’s commission. Whilst the majority of the group liked this idea of complicating the reading experiences for audiences, Eddie and Leah show increasing awareness of how audiences may experience the book. They felt that although the concept worked, that audiences may not understand it without providing some explanation or interpretation. We also see in this scene a more nuanced curatorial relationship between the group and Mark. Whilst Eddie is not yet fully on board with the idea, he says “we can only tell him we don’t quite get it and it’s up to him to make it work” indicating that he now understands he cannot tell Mark what to make, but his job is instead to provide guidance and ensure Mark is thinking about the bigger picture – the audience experience. Eddie’s comment here was incredibly reminiscent of curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist in conversation for The Journal of Visual Culture; “At the end of the day it comes down to what the artists want to do, and as a curator I just help configure it.” (2013, p.149).

Another challenge Mark had with his commission was how this book would be displayed in the gallery. The group were clear that the book should be displayed in an engaging way that urged audiences to interact with it. For me, this is when Mark’s commission moved from the realm of creating a publication to producing an art installation. More on the books final display in the next act.

Another challenge Mark had with his commission was how this book would be displayed in the gallery. The group were clear that the book should be displayed in an engaging way that urged audiences to interact with it. For me, this is when Mark’s commission moved from the realm of creating a publication to producing an art installation. More on the books final display in the next act.

including existing artwork

So far I have detailed how the group worked to interview and commission artists for the exhibition, but they also included one existing piece of artwork in their show by artist Alaena Turner. I first met Alaena at Slade School of Fine Art, University College London, as we were both exhibiting work in a show titled Against Delivery (2015). Alaena also happened to be a PhD student at the University of Leeds undertaking a practice-led study in painting. Months later I did a presentation for the group about exhibitions I had been a part of and showed some footage from Against Delivery. The footage scans across the exhibition and features Alaena’s dynamic installation which immediately got the groups attention. “Wow! Did you just see that! That painting fell off the wall!” shouted Diana. “What’s just happened!” asked Hannah, “Let’s see that again!”. “Don’t worry! It’s suppose to happen, Alaena sets up the paintings to do this on purpose”. “That’s sooo cool” Tony replied, “I wanna do that”. From this brief piece of footage the group were very keen to try out Alaena’s painting techniques and learn more about her work, so I invited Aleana to a workshop.

Unfortunately for us, Aleana lives in London and so travel was extremely expensive. As we were not able to cover her expenses at that time, we instead corresponded with Alaena over several months via email and Skype. During one of our correspondences, the group had asked Alaena to film herself making a Secret Action Painting, as they were interested in learning about the process. This video shows Alaena in her studio. A painting is hung in the background and Alaena approaches with another smaller painting and mounts it over the top. The camera is left running and we see the painting slowly moving down leaving sticky black marks. Alaena’s work immediately resonated with the group. I think it’s because Alaena’s work is so unpredictable. It really does fill you with feeling of anticipation as you wait for the painting to drop, BANG!

Unfortunately for us, Aleana lives in London and so travel was extremely expensive. As we were not able to cover her expenses at that time, we instead corresponded with Alaena over several months via email and Skype. During one of our correspondences, the group had asked Alaena to film herself making a Secret Action Painting, as they were interested in learning about the process. This video shows Alaena in her studio. A painting is hung in the background and Alaena approaches with another smaller painting and mounts it over the top. The camera is left running and we see the painting slowly moving down leaving sticky black marks. Alaena’s work immediately resonated with the group. I think it’s because Alaena’s work is so unpredictable. It really does fill you with feeling of anticipation as you wait for the painting to drop, BANG!

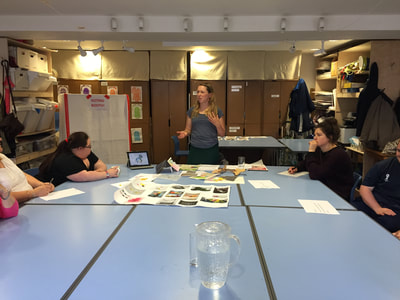

In conversation with Alaena, we decided to try and run a workshop remotely. In this workshop we attempted to recreate Alaena’s Secret Action Paintings as a way to better understand them. On the surface they look deceptively simple; painted wooden boards, stuck together with a glue which doesn’t quick stick enough, so the painting slips, leaving traces of paint. Alaena’s work also features pastel shades or as Alaena describes “muted colours”- not colours the group usually gravitate towards. I urged the group to try this new palette and what we learnt is that soft pastel colours are actually much trickier to mix. “Well she must have practiced a lot, because this is annoying me now. It still dead orange” complained Eddie. “It is isn’t it! I’m going off pastel pink” said Diana. After a lot of paint mixing, the group finished their boards and we set them to dry over lunch.

Curators skyping Alaena, 2016

Curators skyping Alaena, 2016

After lunch, we began on composition and mixing the secret recipe glue. The group all found the composition straightforward, but mastering the glue was hard. Too thick, too thin, not sticky enough, too sticky, we all realised that Alaena’s work was much more complex than meets the eye. Conversation turned to how this might be evidenced in the show. “I just don’t think people know until you do it. Is there a way we can give people a go?” asked Leah. This was the first time the group - without me prompting - were thinking of engagement events and ways for the audience to understand the materiality of the work. After we tried (but sort of failed) with the glue, we had arranged to skype Alaena to show her our work. “Couldn’t do it, couldn’t make it stick” Tony explained to Alaena. “Yes, well it is my secret recipe” said Alaena with a grin. Alaena talked through how she would like to see her work installed at the show. Originally, the group were keen to have Alaena create the Secret Action Paintings live, but this threw up a myriad of health and safety problems, as well as unanticipated costs. In response, the group suggested including a video of Alaena making the work alongside her static paintings, but initially Alaena was a little unsure as for her, video was uncharted territory, but was open for them to try out video ideas. The solution came with the development of the exhibition interpretation which I shall discuss in the next act.

[1] On the 13th February 2015 I accompanied Leah and another self-advocate to interview 3 learning disability community nurses in Widnes.

[2] 3 votes for James, 1 vote for Joe and 1 vote for Becky.

[3] Auto Agent Bob was used again in a workshop at the 2016 Engage Conference: Art & Activism to discuss the challenges in navigating the curator/artist relationship.